The history of Islam and Muslim people in the Caribbean stretches back over 1,000 years, predating European contact by over 600 years. New research is revealing evidence of Muslims in the ancient Americas long before Columbus’s voyages in the fifteenth century, says Muhammad Yasin Khan.

1. Pre-Columbian Muslim Voyages and Early Trans-Atlantic Contact

MUSLIMS WERE PROBABLY ONE OF the most important contact people between the two worlds with the exchange of knowledge, agricultural products, livestock and other commercial items. A number of sculptures, oral traditions, eyewitness reports, artefacts, and inscriptions have been sighted to confirm this.

A report in “Before Columbus” by Cyrus Gordon describes coins found in the southern Caribbean region off the coast of Venezuela. Two of these coins are Arabic and date to the eighth century AD. The author infers that a Moorish ship, perhaps from Spain or North Africa, seems to have crossed the Atlantic around 800 AD. In Mutirj adh-Dhahab, Al Mas’udi wrote in 956 AD about a young man from Cordoba, Spain, named Khashkash Ibn Saeed Ibn Aswad, who crossed the Atlantic Ocean and returned in 889 AD. (Note: The author of this article states that he saw a Moroccan coin, dated in the 12th century CE, found off the coast of Venezuela, at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.)

A narration by Abu Bakr b. Umar al Qutiyya relates the story of Ibn Farrukh, who landed in February 999 AD in Gando (Great Canary), visited King Guanariga, and continued his journey westwards until he found the islands he called Capraria and Phitana. Al-Sharif al-Idrisi (1097–1155 AD), the famous Arab Geographer, reported in his extensive twelfth-century work “The Geography of Al Idrisi” on the journey of a group of North African seamen who reached the Americas. Al-Idrisi recorded that, after three days in captivity, a translator arrived who spoke Arabic and translated for the King, who questioned them about their mission. This astonishing historical report clearly confirms that contact between the two worlds was so extensive that native people could speak Arabic!

2. West Africa and the Atlantic: The Expeditions of Mali

A 14th-century European depiction of Mansa Musa, the famous Mandinka ruler of the Mali Empire

In October 1929, a parchment map was discovered in the library of Serallo in Istanbul, dating to Muharram 919 AH (March 1513 AD). This map represented the western zone of the world. It comprised the Atlantic Ocean, America, and the western rim of the world. The other parts of the world, which the map undoubtedly also included, have been lost.

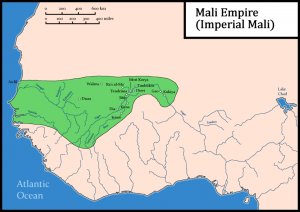

Despite the numerous voyages taken by the Muslims of Spain and North Africa, their contact remained limited and fairly secretive. The most significant wave of Muslim explorers and traders came from the West African Islamic Empire of Mali. When Mansa Musa, the world-renowned leader of Mali, was en route to Makkah during his famous pilgrimage in 1324, he informed the scholars of Cairo that his predecessor had undertaken two expeditions (the first with two hundred ships and the second with two thousand ships) into the Atlantic Ocean in order to discover its limits. Al’Umari reports this in his “Masalik al-Absar fi Mamaluk al-Ansar”.

3. Mandinka Footprints Across the Americas

Territory of the Mali Empire

The renowned American historian and linguist Leo Weiner, of Harvard University, wrote in 1920 a controversial but well-documented work entitled “Africa and the Discovery of America”. He proved that Columbus was well aware of the Mandinka presence and that West African Muslims had not only spread throughout the Caribbean, Central, and South America, but also reached Canada, where they traded and intermarried with the Iroquois and Algonquin Indian nations!

Numerous cultural evidences of Mandinka presence have been established in Brazil, Peru, Panama, Nicaragua, Honduras, Mexico, Mississippi and Arizona. In the “Daily Clarion” of Belize on November 5, 1946, P.V. Ramos in an article entitled “History of the Caribs”, wrote: “When Christopher Columbus discovered the West Indies about the year 1493 AD, he found there a race of white people (i.e. half-breeds) with woolly hair whom he called Caribs. They were seafaring hunters and tillers of soil, peaceful and united. They hated aggression. Their religion was Mohammadism and their language Arabic”.

This reveals another part of the pre-Colombian African hereditary legacy left with the Carib people, from whose name we derive the word “Caribbean”.

4. Muslims in Chains: Enslaved African Muslims in the Caribbean

The second presence of Muslims was Africans kidnapped by or sold to European slave traders and transported from West Africa to a “new world” of oppression and inhumanity. Over a 300-year period, millions of Africans were transported in what must be one of the most barbarous and atrocious episodes in human history. Historians usually ignore the fact that many of these enslaved Africans were Muslims. Many of them came from predominantly Muslim African nations, such as the Mandinka, the Fula, the Susu, and the Hausa, and there are indications that some were distinguished scholars of Islam.

5. Literacy, Faith, and Resistance Under Slavery

5. Literacy, Faith, and Resistance Under Slavery

Despite the inhuman system of slavery in the Americas and the forced separation from Islamic lands and culture, there are scores of reports of enslaved Muslims maintaining a form of their faith, leading slave revolts and in some cases regaining their freedom and returning to Africa. The leading force among the enslaved Muslim Africans was the Mandinka, known in the Americas as “Mandingo”. They were found in considerable numbers in Jamaica, Trinidad, St. Vincent, Venezuela and other Caribbean nations.

Alex Haley in his book “Roots” recreates graphically the story of his Muslim ancestor Kunta Kinte, who was kidnapped, sold and transported to the Americas. Besides exposing the atrocities and cultural genocide perpetrated by the “civilised” European colonisers and the manner in which Christianity was used to subjugate and pacify slaves in the interest of the plantation exploiters, Haley’s work also shows the attempts made by the slaves to cling to their Islamic culture and heritage and the impact of this legacy on the author himself.

6. Muslim-Led Slave Revolts and the Spirit of Jihad (struggle for justice)

In Jamaica, special magistrate Robert R Madden, one of six special magistrates sent to the island in 1833 by the British government, recorded not only the presence of a considerable amount of Muslims in Jamaica, but also found them to be generally literate, independent and “rebellious”.

In his book “A Twelve Months Residence in the West Indies during transition from Slavery to Apprenticeship”, Madden narrates the moving stories of Anna Moosa and Abu Bakr Sadiqa who persisted in maintaining their Islamic faith under adverse and hostile conditions. Abu Bakr, Anna Moosa, and others had formed a society and had requested that Madden assist them in developing African schools for African people in Kingston.

In Trinidad, the African Muslims not only formed a “Mandingo Society” but also established schools in Port of Spain. They were led by one Jonas Mohammed Bath. Others settled in south Trinidad and in Monsamilla (Manzanilla) in the northeast. They were given land and developed their own plantations. They made great economic strides and petitioned the British government to repatriate them to Africa.

One of the petitions addressed to William IV, King of Great Britain and Ireland (reign from 1830 – 1837), began with the phrase “Allahuma Sallee ‘ala Muhammad” (O Allah, bless Muhammad). It explained that the petitioners were followers of Muhammad (pbuh), the Messenger of Allah, and that they did not waste their wealth on intoxicants as other slaves were accustomed to.

There is ample evidence to indicate that African Muslims in the Caribbean were at the forefront of the struggle to resist slavery. In Jamaica, R. Madden was also informed about a paper (Wathiqah) written in Africa in 1789 AD, “which exhorted all the followers of Muhammad to be true and faithful if they wish to enter Paradise”.

A Jihad called the “Great Slave Rebellion” of 1834 broke out in Manchester Parish, Jamaica. The documents had to be destroyed in the heat of the rebellion, but the spirit of resistance continued to be rekindled in the hearts of slaves. In Haiti, from 1753 to 1757, Mackandal, a Muslim religious leader, led numerous raids against the plantation owners. Mackandal’s campaign directly led to the Haitian Revolution in 1791, which was led by Toussaint L’Ouverture.

In Brazil, the slave uprisings and rebellions between 1807 and 1835 have been substantiated as being a well-organised Jihad by Hausas who were resisting “the enslavement of Allah’s children by Christians”. The Jihads hastened the process of abolishing slavery in Brazil.

The “Bush Negroes” in Surinam, led by Arabi and Zam-Zam, defeated the Dutch on many occasions and were finally granted a treaty and their own territory (near French Guiana), which they have controlled to this day.

All these Muslim groups have been submerged almost without a trace. The near elimination of Islam among African slaves has been one of the major “achievements” of European colonialism and Christian missionaries.

7. From Slavery to Indentureship: A Second Muslim Migration

Difference Between-Indentured Servants-and Slaves Comparison-Summary

Between 1838 and 1924, a new element was introduced into the Caribbean population through indentureship. Nearly half a million “East Indians,” as they were called, entered the region, mainly Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname, but also Guadeloupe, Martinique, Jamaica, St Lucia, St Vincent and Grenada.

Nine-tenths of the indentured Indian immigrants were from the Ganges River basin and embarked from Calcutta, with the remaining 10% from Madras, southern India. One out of six was a Muslim, the rest mostly Hindus.

The Spanish brought in Chinese contract workers into Cuba, and the Dutch introduced workers from the Netherlands Indies, principally Java.

The latter, who were mainly Muslims, were taken to Suriname.

Despite clear conditions and a commission of enforcement, the indentured labourers were severely abused and exploited. The conditions under the indentureship system and on the plantations – long working hours, low wages, the discouraging and even hostile attitude on the part of plantation owners and Christian missionaries – did not afford much opportunity for community development. In actuality, the living conditions were very similar to those of the slaves, and harsh treatment was common throughout the territories.

8. East Indian Muslims and the Struggle to Preserve Faith

The Indian Muslims had come primarily from the illiterate class and co-existed with the Hindus. They were not able to transplant Islamic communal life with them from India, and they became targets of hostility from every angle. This may well be illustrated by the fact that they were called the Muslims “Mandingos” and in Guyana “Fuller-man” (for Fulani) in a derisive manner thereby underlying the fact that the “Indian” Muslims had more in common with the “African” Muslims from the Mandinga and Fulani tribes of West Africa and also showing incidentally that they were surviving African Muslims of slave origin even after abolition of slavery and up to at least 1850. For example, Muslims who congregated to offer Eid prayers on the Palmiste Estate in South Trinidad were flogged for offering their first Eid prayers in the land.

By 1865, the Indian Muslims of the Caribbean began making organised efforts to resist the hostility and oppression around them. The first mosques in Guyana were built of mud and grass (tapia) or wood and covered with palm leaves. To these mosques were added “Maktabs” to provide Islamic education for children. The “Maktabs”, however, were ill-equipped, lacking both material and human resources and barely managed to maintain the rudiments of faith by revolving themselves around such festive occasions as the Prophet’s (pbuh) birthday (Milad-un-Nabi). When the system of indentured labour was abolished in the first half of the twentieth century (in May 1917), Muslims were able to build more masjids across various communities.

9. Racial Politics, Identity, and the “Indianization” of Islam

As a result of the atmosphere of hostility confronting Muslims, they reacted by becoming very introverted and inward-looking. The community became concerned only with self-preservation during this period. Little or no effort was made in propagating Islam as a complete way of life. Unfortunately, this resulted in the projection of Islam being identified as an “Indian religion” by people of African descent in particular.

This image of Islam was further escalated in Trinidad and Guyana when Muslims interacted with Hindus on the basis of a common Indian identity for events. This was especially true in the immediate pre- and post-independence era, when Indians perceived dangers posed by African political domination. Developments in Guyana well illustrated the polarisation of African-Indian racial politics.

In Trinidad, there have been some curious cases of Indians (mainly Muslims) who have supported African majority parties but who simultaneously made strong appeals to a common Hindu-Muslim Indian identity.

A prominent example of this kind of politician is Kamaluddin Mohammed, a former member of parliament (for 30 years in the second half of the 20th century), who – as a founding member of the People’s National Movement and chairman of the Nur-e-Islam Mosque board – is referred to as “the father of Indian culture on the island.” He has been asserting that “(the Hindus and the Muslims came together (to the West Indies) as one people” and that Islam and Hinduism “are very closely linked with each other.”

The practice of trying to forge links between Muslims and Hindus on the basis of a common Indian culture, clearly manifested in the numerous Indian programmes on radio and television, has been one of the major drawbacks in presenting a proper image of Islam (i.e. it is not based on race) to the people as a whole.

Inevitably, however, the Muslims were not able to withstand all the pressures which living in a plural society involved, societies moreover in which they were a minority. Although Muslims in this period managed to establish organisations, primary and secondary schools, and a few basic institutions, these were inadequate for serving the needs of an emerging community. On a wider plane, in the major areas of economic and political life, the Muslims as a body were not able to make any distinctive contribution. Although there were ministers in governments and Muslim members of parliament, the Muslims rarely saw fit to put forward Islamic ideas and programmes.

10. Arab and Javanese Muslim Communities in the Caribbean

Apart from Muslims of Indian descent in this period, Muslims from Java, brought by the Dutch and settled in Suriname, isolated themselves from the rest of Surinam and Caribbean society. They have chosen to remain aloof or return to Indonesia rather than become a functional part of Caribbean society. In some countries, immigrants from the Middle East settled mainly from Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine. There was a very small percentage of Muslims in this Middle Eastern migration, but like their counterparts, they became totally absorbed in business and had little to do with religion. Only on a few islands like Curacao and St Croix (US Virgin Islands), and in Panama, is the presence of Arab Muslims recognisable in the region. There, they have assisted in building Islamic centres and Masjids and have funded scholars from the Middle East.

11. Foundations for Revival: Institutions, Education, and Organisation

This period at least resulted in a sustained presence of Muslims in the Caribbean and laid the basis on which an Islamic re-awakening has taken root today. Recent developments have only highlighted the need for a more organised and systematic approach to Islamic work in the region (i.e., building institutions and systems to serve the faith community and others).

This article is a slightly edited version of an article published in MuslimWise magazine in July 1990.