As published by New York Times here

ENTERPRISE, Trinidad and Tobago — By the time he was 17, Fahyim Sabur had memorized the Quran.

At 23, he was shunning calypso parties and giving private Arabic lessons in his neighborhood here in Enterprise, about 20 miles south of Port of Spain, the capital of Trinidad and Tobago.

A year later, he was on the battlefield in Syria, where he died fighting for the Islamic State.

“He never spoke to me about it,” said his father, Abdus Sabur, 56, who sells meat patties on the street. “National Security called me one day and told me, ‘Your son is dead.’ ”

Law enforcement officials in Trinidad and Tobago, a small Caribbean island nation off the coast of Venezuela, are scrambling to close a pipeline that has sent a steady stream of young Muslims to Syria, where they have taken up arms for the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL.

American officials worry about having a breeding ground for extremists so close to the United States, fearing that Trinidadian fighters could return from the Middle East and attack American diplomatic and oil installations in Trinidad, or even take a three-and-a-half-hour flight to Miami.

President Trump spoke by telephone over the weekend with Prime Minister Keith Rowley of Trinidad and Tobago about terrorism and other security challenges, including foreign fighters, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, a White House spokeswoman, said.

Trinidad has a history of Islamist extremism — a radical Muslim group was responsible for a failed coup in 1990 that lasted six days, and in 2012 a Trinidadian man was sentenced to life in prison for his role in a plot to blow up Kennedy International Airport. Muslims make up only about 6 percent of the population, and the combatants often come from the margins of society, some of them on the run from criminal charges.

They saw few opportunities in an oil-rich nation whose economy has declined with the price of petroleum, experts say. Some were gang members who either converted or were radicalized in prison, while others have been swayed by local imams who studied in the Middle East, according to Muslim leaders and American officials.

The young men found solace in radical Islamist websites and social media.

And in the call to jihad.

In contrast to the laws of many countries, it is not illegal in Trinidad to join the so-called caliphate, though the government wants to change that. One hundred to 130 people have made the trip to Syria from Trinidad, which has a population of 1.3 million, according to a former United States ambassador, John L. Estrada, and Trinidad’s minister of national security, Edmund Dillon.

By comparison, about 250 citizens of the United States, a country with 240 times the population, had joined the extremists or attempted to travel to Syria by late 2015, according to a House Homeland Security Committee report.

Per capita, Trinidad has the greatest number of foreign fighters from the Western Hemisphere who have joined the Islamic State, said Mr. Estrada, who stepped down after the inauguration of President Trump last month.

“Trinidadians do very well with ISIL,” Mr. Estrada said. “They are high up in the ranks, they are very respected and they are English-speaking. ISIL have used them for propaganda to spread their message through the Caribbean.”

Much of the information about the identities of those who went abroad comes from American intelligence sources, although local imams and Islamic leaders all said they knew several people, including women, who had left.

Imtiaz Mohammed

“I know whole families that went,” said Imtiaz Mohammed, president of the Islamic Missionaries Guild, which does charity work in Trinidad and the Middle East.

Juan S. Gonzalez, a former deputy assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere affairs, said the bulk of Islamic State fighters from Latin America originated in Trinidad and Tobago. The numbers underscore a risk of lone-wolf attacks in the region, he added.

“As the United States continues to corner ISIS and defeat them, a lot of these guys aren’t going to feel they have safe quarters,” Mr. Gonzalez said. “Is the Caribbean, Trinidad and Tobago, the United States, prepared for these guys to return back to their countries? This is a real vulnerability.”

He noted that people in the Caribbean enjoyed visa-free travel throughout the islands, which makes it fairly easy to travel to the Bahamas, and from there make a “short jump” to South Florida.

The United States, which encouraged Trinidad to tighten its laws, has hosted meetings with Muslim leaders at the embassy in Port of Spain, and paid for several to attend anti-extremism workshops in the United States.

Mr. Sabur, the young radical from Enterprise, is one of a handful of Trinidadians known to have died in Syria. Others include Shawn Parson, who appeared in an Islamic State recruiting video. He was targeted by an F.B.I. program that, with the cooperation of the military, sought to eliminate the group’s social media figures, often with drone strikes.

Last summer, Shane Crawford, also known as Abu Sa’d at-Trinidadi, perhaps Trinidad’s best-known Islamic State recruit, was prominently featured in an article in the group’s magazine, Dabiq, in which he called for attacks on Western embassies.

Mr. Crawford said he had been influenced by Islamic lectures and a Trinidadian Muslim leader, Ashmead Choate. Mr. Choate “attained martyrdom” in Ramadi, Iraq, the article said.

The genesis of today’s rising militancy, Mr. Crawford added in the article, can be traced to the failed 1990 coup, when a group of radical Muslims took legislators hostage in a siege of Parliament. When it was over, two dozen people were dead.

Yasin Abu Bakr, 76, who led that uprising and has since been released from prison, said the government had created a climate where young Muslims did not feel safe or welcome in the military or civil service. “This is total discrimination and isolation against young Muslims in Trinidad,” he said in an interview.

Trinidad’s attorney general, Faris Al-Rawi, said that after the coup, wearing Muslim garb “took on a certain appeal.”

“A lot of people who were not genuinely Muslim or otherwise took on the persona to carry on their thuggery,” he added.

Mr. Al-Rawi said Mr. Crawford was believed to have died in Syria. His mother, Joan Crawford, said she had heard rumors that he had been badly wounded.

Ms. Crawford, 62, said that her son had been falsely accused of plotting to kill the Trinidadian prime minister, and that this had diminished his professional prospects, even though he ran a fish business and had experience in plumbing.

“Once you are branded a terrorist in your own country, what could you do?” said Ms. Crawford, a former Spiritual Baptist who converted to Islam after her son did. “I did cry, because I knew I would never see him again. I did not get to say goodbye.”

Efforts to combat the flow of young Muslims to overseas battlefields have been complicated by the ambivalence toward, and sometimes support for, the jihadi cause among some imams and the recruits’ parents. In an interview that began and ended with a prayer, Mr. Sabur said he had welcomed his son’s death as a martyr: “I felt elated. Speaking about it now, I am overelated.”

The Trinidadian government last week introduced a series of amendments that would criminalize membership in the Islamic State and other extremist organizations. People who traveled to certain regions would be presumed to be doing so for terrorism, and the burden to prove otherwise would be on them, Mr. Al-Rawi said.

Mr. Mohammed, of the Islamic Missionaries Guild, criticized the proposed legislation, saying groups like his that make trips to the Middle East are often engaged in charity work and could be unfairly singled out.

“You can’t just go to a court and have a judge tell you that you are guilty with no evidence, just an assumption,” he said.

Mr. Mohammed has publicly denounced the Islamic State, but noted that his own United States visa and commercial pilot’s license had been revoked after a terrorism suspect passed through his Islamic center.

A senior intelligence official in Trinidad who was not authorized to speak publicly said he worried that the proposed legislation would make people who would have left for Syria plan attacks at home instead.

He said about 15 or 20 of the Islamic State recruits spent two weeks before their trips at a mosque in Rio Claro, about 50 miles southeast of Port of Spain. There, they attended an orientation, the official said.

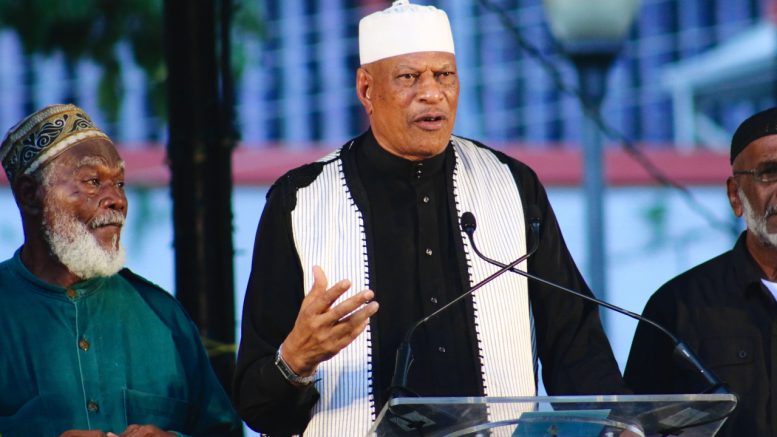

Umar Abdullah

Umar Abdullah, an Islamic activist, said he had been among those who encouraged the would-be fighters.

Despite having made thinly veiled threats to Americans in the past, which led a cruise ship on its way to Trinidad to turn back, Mr. Abdullah has since denounced extremism, and now says Muslims must work with the United States to “change the narrative.” It would be “stupid” to try to attack the United States Embassy, he said.

“At one point in time I was a strong believer in that, and I still believe it to some extent,” Mr. Abdullah said. “But to do something like that would put the Muslim community in harm’s way. We would not be able to stand the fallout of that type of action.”

The imam in Rio Claro, Nazim Mohammed, denied running an Islamic State training program, and insisted that he operated an elementary school and a weekly food program for the poor. But he acknowledged that two of his children and five of his grandchildren were in Syria, and that the adults were believed to be involved with the Islamic State.

“Killing and murdering is not Islamic,” Nazim Mohammed, 75, said in an interview. “Our program is to help people. You know how many people have come here for help?”

He insisted that his children did not notify him of their plans, and he shrugged off the group’s influence.

“Who is ISIS?” he said. “ISIS is just a few people.”

Be the first to comment on "NY Times:Trying to Stanch Trinidad’s Flow of Young Recruits to ISIS"