Introduction

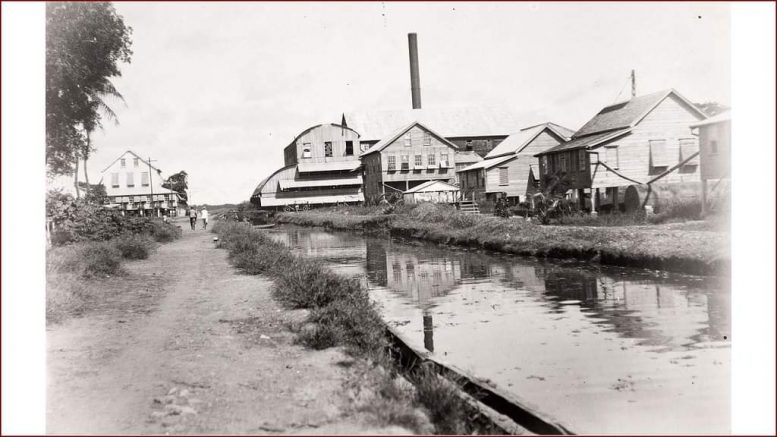

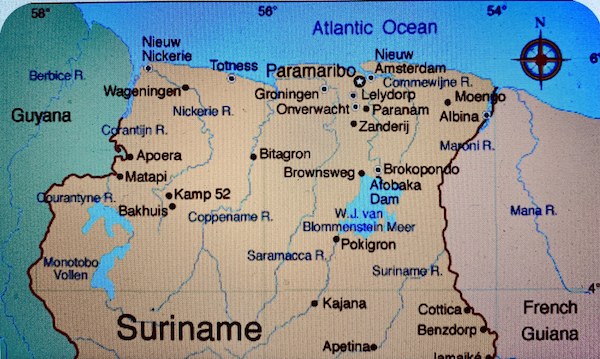

Waterloo was a sugar cane plantation on the Nickerie River in the Nickerie district in Suriname. Nickerie is a district of Suriname, on the northwest coast. Nickerie’s capital city is Nieuw-Nickerie. Another town is Wageningen. The district borders the Atlantic Ocean to the north, the Surinamese district of Coronie to the east, the Surinamese district of Sipaliwini to the south and Guyana to the west. Suriname was settled by the British in the 1630s and alternated between Dutch and British possession until 1815 when the Treaty of Vienna formally awarded it to the Dutch. Waterloo was founded in 1819 by James Balfour. In 1936, Waterloo was bought by Sankar. In 1937, Guyanese entrepreneur Sankar, who owned Hazard, Waterloo, Longmay, Plaisance and Paradise, began planting coconut palms on a large scale for the production of copra and coconut oil. Within a few years, he wanted to have between 60,000 and 100,000 palms. In the early 1950s, about a million kilos of sugar and 12 and 19 litres of rum were still being produced. The strike eventually led to the bankruptcy of Sankar and the closure of the plantation. The conditions were really bad, and the contract workers were not allowed to enter or leave the plantation without permission from the owner. In 1969, a strike was called by Eddy Bruma, which led to the bankruptcy of Sankar and the closure of the plantation. This article seeks to narrate the human cost of bad human resources policies from the workers perspective and the shredding of kinship bonds.

Jehangir Khan represents resilience, the oldest known ancestor of the Esau Khan clan. The marriage of one of his descendants into the Sankar clan reveals a family narrative of the rise and fall of the Waterloo Plantation, and which adds credence to Mr Donk’s paper. Indeed, like Mr Donk said in his study, “Waterloo was Guyana in Suriname.” In doing so, the paper, for the first time, shed light on the family history of one of Guyana’s fascinating and industrious family.

Jehangir Khan represents resilience, the oldest known ancestor of the Esau Khan clan. The marriage of one of his descendants into the Sankar clan reveals a family narrative of the rise and fall of the Waterloo Plantation, and which adds credence to Mr Donk’s paper. Indeed, like Mr Donk said in his study, “Waterloo was Guyana in Suriname.” In doing so, the paper, for the first time, shed light on the family history of one of Guyana’s fascinating and industrious family.

The battle on the Waterloo Plantation

Mr Amin Sankar and his daughter, Lyla Sankar meeting the Queen Picture courtesy Chandi Singh Alumni

An article published in Dutch Researcher by K R. Donk, dated March 20, 2007. The title “The battle on the Waterloo Plantation” caught my attention due to strong ties with Nickerie and Suriname. Mr Esau Khan (nephew of Amin Sankar) was the estate manager for an extended period. Subsequently, the estate was managed by Mrs Zohorah Chan Sankar (aka Joree, wife of the owner of Waterloo), Amin Sankar and her brother, Mr Sama Chan. Many in the community of Waterloo spoke well of Khan and his uncle Amin Sankar. Amin was the brother of Batulan Sankar, also known as Batul Deed (for elder sister). Esau Khan was the son of Batulan, and he went to live and work for his uncle Amin at an early age after the death of his father, Foork Phir Khan, in 1922.

Before the Sankar brothers became wealthy, Esau Khan worked for them in their sawmill and bus transportation business on the Corentyne, Guyana. Esau was the first manager of the estate from the 1930s to 1952. He was born in 1915. By age 19, he managed the Waterloo Estate and travelled all over the Caribbean on business for the Sankars. By 1955, he had relinquished all legal ties to the estate. He also signed all properties over to Amin and Zohorah Sankar when Jagernath Lachmon was their advocate. Then when trouble was brewing in the 1960s, his uncle Amin urged him in a letter to return. He did not

The demise of the Waterloo Plantation can be attributed to human rights abuses at the estate after Esau Khan was removed from that position by Zohorah Sankar. Instead, she brought her brother, Sama Chan from Guyana, and made him manager of Waterloo. Khan received a severance of about 30,000 Guilders from Zohorah. That money went to Khan’s second wife, Alma Pandey who had brought litigation against the Sankars. It would have been wiser if Mrs Sankar had put that money in a trust fund for the children of Esau Khan, especially that their mother had died. Mrs Sankar also severed the school tuition of his children. Esau’s wife, Maryam, died the very night (circa 1950) that Mrs Sankar confiscated the china and flatware belonging to his family. After Amin’s death, Joree (the now matriarch of the Amin estate) turned her back on Khan and his now motherless children.

These issues were narrated in a blog by a son of Esau Khan, who lives in Amsterdam, Netherlands. Also, families like Z. Ally, from the Zaitoon Sankar’s (Amin’s sister) clan who worked at Waterloo, experienced these “inhumane conditions” when these two were running the estate.

According to the author, Mr Donk, Waterloo Plantation was purchased from James Kirke, nephew of the former Scottish slaveholder, James Balfour, in 1934 by the brothers Amin and Ahmad Sankar reportedly for SF 40,000. The Surinamese currency was higher in value than that of the Netherlands during that period.

The Sankar Brothers’ Lineage

There are many Sankars in Guyana, but this family is unique. They were one of the richest families in Guyana and the Caribbean. The Sankar brothers were the first and only Hindustanis to own a large sugar plantation in the Caribbean and maybe the world. The Amin and Ahmad Sankar brothers also owned several cinemas in Guyana and Suriname, the first Mercedes Benz and Volkswagen dealership in Guyana. As well they had owned the iconic Hope Estate that Burnham confiscated. Afficance Park and Maida Estates were also part of their holdings. The name was originally spelt Susankar (birth record # 96), and his brother was Dookie. According to the birth records of his children, Susankar last arrived in Guyana in 1880 as a free-paying passenger. Mr Feroz Dookie of Guyana and his siblings are from this clan.

The Dookie and Sankar brothers were sons of Ramessar, an India-born Brahmin who had married a pious Muslim woman, Khadmi. Sankar and Dookie were raised in Islam by their mother, Khadmi. The boys also had Muslim names, Maula Baksh and Khuda Baksh. In the Guyana Chronicle newspaper, an article commemorating the centennial of the # 78 Mosque in 1963 identified Khadmi as the “mother” of Sankar and Dookie, and she was one of the “founders of the # 78 Masjid, Corentyne.”

Mr Amin Sankar

According to the family narrative and some documents, Sankar’s father, Ramessar, and the two boys, along with his Muslim wife, Khadmi, returned to India. Ramessar had converted to Islam because Khadmi’s father was an Imam. They were not able to hide their Muslim secret. Commotion erupted, and he received his share of the inheritance from India in 1880, he and his family returned to Guyana on a paid passenger line. Ramessar then opened a Goldsmith business in Skeldon. He very well could have been the first goldsmith in Skeldon.

The Guyana Chronicle in 1963 said, “Extensive and exhaustive research has revealed that the mosque was built in 1863 by Sohabeth Subrati, father of the late Moulvi Ibrahim, as well as Ishmile Shahabuddin, Wajid Ally and Begum (Mrs) Khadmi, mother of Messrs, Dookie and Sankar. These people “evinced and shown keen interest in Islam, and it was by their instrumentality that they have been fortunate to acquire a piece of land and built a small mosque.” Women like Begum Khadmi and others have remained silent in our narrative, but hopefully, people will start writing more about women’s role in nurturing their families and the community.

Sankar was married to Sakinatul, misspelt Saakonty on her immigration pass. Sakina Khatoon came as an infant to Guyana from Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh with her mother, Goolonia. She was kidnapped with her infant daughter and sent to Calcutta, waiting to be shipped to Guyana on board the King Arthur in 1878. They were indentured to Plantation Eliza and Mary, now known as Skeldon. Goolonia Khatoon and Sakinatul Khatoon were practising Muslims who wore head-covering. She was a human rights advocate for “bound collies” at Plantation Eliza and Mary. This couple are the parents of Isahaq, Azeez, Hashim, Shaheed, Yaseen, Amin, Ahmad, Batulan, Najmun Nissa (Zaitoon) and Zaibunissa Sankar.

Of interest, Goolonia, when she arrived at Skeldon after three years, married Karamat Khan, who she had met on board the King Arthur. They had two sons, Qabil (1881) and Noor Khan (1882), but on the birth records, Qabil was spelt “Kabul,” In addition, she had three children with Rustom Khan after Karmat Khan died. They were Nur Khan (1884), Shehzaadi (1892) and Zainab (misspelt and pronounced in Guyana as Jainab). This is a regional accent where in some parts of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, people can’t pronounce the Z and instead say “Ja” like in Jainab, Nijam or Jaitoon instead of Zainab, Nizam and Zaitoon. Eventually, these three sisters would marry into three big families in Skeldon. Sakinatul married Sankar, and they had 9 children; Shehzaadi, also known as Saijaadi, would marry Abdool Rahaman, and they had a large family. Qabil, Nur Khan, and Ghanim Khan also elevated themselves into big accomplished clans in Guyana.

Zainab, the youngest sister, was married to Ibrahim Majee, the son of Sobrattee Husain. Sobrattee, as he was locally known, was indentured to Eliza and Mary. He came on board the Aurora in 1859, three years before the # 78 Masjid was built. He likely came with a brother of his, Sohobat. Hence, the 1963 article should have read, “Sohobat and Sobrattee.” They are two different people. He was one of the leading figures involved in the building of the Masjid in 1863. The original site of the mosque was at #79 Village, where Mohammed Ezammudeen lives today. The mosque was moved to its current location at # 78 Village. Sobratee left many offspring in Guyana; three of his sons were Imams. We know of two, Moulvi Abdool Kareem and Moulvi Ibrahim.

According to Mr Donk, “In the 1930s, Sankar was a small trader who sold goods, including bloem (flour), onions, burlap bags, from Guyana in Nickerie. Before Khan began managing the Waterloo Estate, he was managing one of the Sankar’s stores located next to the Julianatheater on Gouvernestraat, Nickerie. A certain Samlal, who lived on the former Paradise Plantation in Nickerie, then one of Nickerie’s richest Hindustani, helped him buy the plantation in 1934.” Sankar also bought Juliana Cinema. In addition, Amin’s cousin Edris Dookie also owned a store in Nickerie, and other siblings of the Dookie clan had holdings in several estates in Guyana.

Meanwhile, Mohammed Ashraf Dookie and one of his sons, Feroze Dookie, lived on and managed the Maida Coconut Plantation. Eventually, another sibling of Esau Khan, Bibi Haniffa Khan and her Suriname-born husband, Awad Hussein Isahaq, became managers of the Maida Estate. Ultimately, by the early 1970s, the Sankar brothers divided their holdings. Maida went to Ahmad and Hope to Amin. Ahmad’s son Atta Bey Sankar was his power of attorney and very well could have been the person or an “agent of Sankar” who allegedly sold the title of the Maida Estate to Mr Muneer Khan, son of J. M. Khan. There were intermarriages between these clans. The land was sold without consulting the descendants of Batulan Khan (Sankar), who were still living at Maida and found themselves landless and homeless, and again doubled crossed by the Sankars in Georgetown. Interestingly, it is alleged that Mr Lyla Sankar, in Georgetown, is donating a plot of land on Main Street belonging to Amin Sankar to charity. Charity begins at home, and the extended family should have been involved in this decision.

Jahangeer Bux Khan 1875 of Maryville, Leguan and Vergenoegen

Much has been narrated about Esau Khan’s maternal ancestors. On his paternal side was his grandfather, Jahangeer Bux Khan, an ethnic Indian Pathan. Khan was absent from his immigration pass, but when his son, Foorkhan, was born, the name Khan was registered as his surname. Jahangeer left India on August 26, 1875, from Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, and arrived in Guyana three months later. His father was Sahadat Khan, and he also had a brother, Mussaffar. At age 24, he came as a single man and married Meenuth, the daughter of Yarally. They were shipmates. She arrived with her husband Mustaqim, from Gazipur, Uttar Pradesh. Mustaqim and Meenuth migrated as a family with their son Siddiq and daughter Moddikum. They were all indentured to Plantation Maryville on Leguan Island off the Essequibo Coast. They all congregated in the “Muslim quarter” of the island where the 1934 mass murder occurred.

When Jahangeer came to Maryville in 1875, less than ten Muslims were on that plantation. By 1885 the Muslim population had increased tremendously; by 1910, Leguan became a significant Muslim settlement. The Jahangeer family was one of the early Muslim families to have settled in Leguan. Soon after Mustaqim arrived in Guyana, he died, and Meenath and Jahangeer then got married. From records found, they had six children, Mohammed Sahil (May 30, 1879), Estarah (1880), Jumarati (December 17, 1882), Majidan (April 1, 1886), and Foorkhan Khan, also spelt Ferkhan and which should really have been Phir Khan, (February 28, 1887). The youngest was Subratti (April 10, 1889). Land records indicate that Subratti registered land he owned in 1933. Like many Indians, their names were misspelt and bastardized. Many Indians ended up with only one name.

The people of Waterloo built this mosque with funds collected from the community.

Both Meenath and Jahangeer died the same week in May of 1892, tragically leaving the children orphans. However, their eldest India-born brother, Saddiq and their elder sister helped raised their young brothers and sisters. By this time, they had also purchased a property on mainland Vergenoegen/Philadelphia. Most likely at Long Dam because Nani Bibi Shahara was born there. Eventually, some of the Jehangeer children lived in Leguan, the East Bank Essequibo and West Coast Demerara. Phir Khan was in the lumbering and cattle businesses and was married to Batulan Sankar around 1914. This was an alliance between two industrious and accomplished families that had holdings in businesses in Guyana and Suriname. Phir Khan tragically died in 1922 due to injuries he sustained during a robbery in which he fought back. He had a large sum of money in his possession.

Interestingly, Phir Khan’s brother, Subratti, was married to Imaman also from Mary and Eliza Plantation, Corentyne. Phir Khan, his brother, was also married to a woman from Corentyne, Batulan. They were married by Imam M. S. Hosein in Peters Hall, Georgetown. Among their children were Ameeran and Nazir. Subratti was an immigration officer, a marriage officer and a Justice of Peace. He eventually moved to Georgetown. Records indicate that he saved money at a bank in Georgetown.

Jehangeer’s children were the same generation as Bora Jaan, Abdul Gaphur, J. M. Khan, Haniff Khan and Baj Khan of Leguan. Phir Khan’s wife, Batulan, kept close ties with families on the West Coast and in Georgetown. Majidan, the sister of Phir Khan, was married to Nabibaksh Khan of Wakenaam, and when he died early, she married Habib Khan and records found that among their children were three sons, Mohammad Abdul Rahaman Khan (Born 1916), Mohammad Abdul Rahim Khan (1902) and Mohammed Abdul Yakoob Khan. Majidan and Nabi Baksh settled in Vergenoegen.

The author ascertained that some of Jahangeer’s descendants, based on oral family and historical records, are in Canada. Bibi Shahara (Saira Nani) was the daughter of Siddiq, born at Long Dam, Vergenoegen, and eventually moved to Zeeburg. It was her father that raised all his siblings. For this reason, Bibi Shahara kept close ties with their family in Corentyne. She always brought the younger generation with her to Corentyne when she visited Bibi Haniffa, Esau Khan and Amzad Khan, the children of Foorkhan. The children of Nani alive today are Jabbar, Zaffar, Rafikan and Maryam from Zeeburg, WCD. Omar died some five years ago. The author’s DNA is linked to the Feroze family of Tushen five generations back. Feroze was married to Shafeek’s sister Khatijan. The Shafeeks had owned a bakery on the West Coast Demerara (WCD). They also have roots in Maryville, Leguan.

Mohammad Abdul Rahim Khan (Short Khan) of Vergenloegen was the son of Majidan, and he had several children- Naymun Nisa, Omar Khan, Halima Rehana Khan and Shireen. They all moved to Canada and Maryland.

Mohammad Abdul Rahaman Khan (Uncle Lama) moved to Bartica, and he was married to Bibi Ayesha, whose mother was Majidan from Ladestin. Ayesha’s brother, Uncle Yusuff, also from Leguan, was married to Hazra Dildar. They all settled in Good Hope.

Mohammed Yacoob Khan was the other son of my Majidan. He died young and had a son, Gool Mohammed Khan, with his wife, Ayesha. She remarried and had several more children with her second husband in Hague.

Summary

In his article, Donk spent a great deal of time documenting the labour unrest of the late 1950s to 1970. Poor working conditions, exploitative salary, long working hours, and arrogance of the new manager Mr Sama Chan motivated the workers’ protest. He spoke of “a feudal system” in which the “children” would no longer accept the status quo, and especially after the Hindustani film, Paigham, was released. “Strict feudal relations prevailed, which eventually destroyed Waterloo. There were allegations that the factory had “inadequate control and inspections for dangerous conditions.”

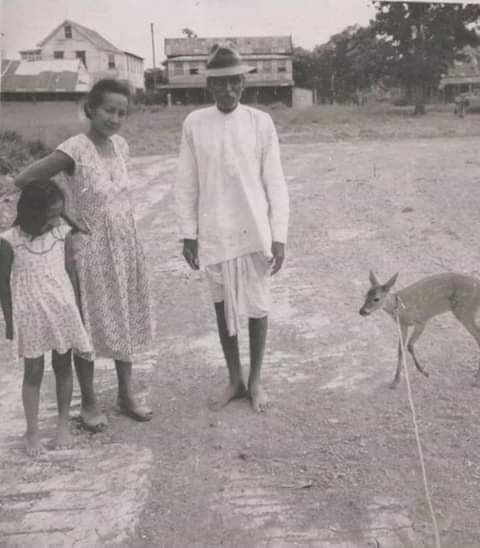

Unidentified persons at Waterloo

“Sankar was legally strong, and he had the best lawyers available. However, the workers had accumulated resentment due to the years of exploitation. There was also a new awareness of the introduction to better working conditions of other employees.”

“The Waterloo children were no longer willing to live and work under the same feudal relationships, which their parents had to accept. The end came quickly.” Yet, some in the Sankar clan who had the Money, felt that the workers had nothing and came from poverty that should have been grateful to them and accepted the status quo.

On December 20, 1969, due to its poor financial standing Waterloo Plantation was closed. The Sankar clan left for Guyana, and Waterloo remains closed forever.”

Living relatives recall well the many people who were interviewed during Donk’s investigation of the rise and fall of Waterloo. Many of the interviewees for the article are familiar with living relatives, and some have kept ties to this day. They believe that workers had legitimate grievances, and most of the events documented in this article are accurate.

Some of these people involved in Donk’s paper are- Rannie Brown of the Nickerie Workers Union, the Santoe brothers; the chairman Ali Zafdar, the sub-chairman Soegriemsing Sewcharansing, the treasurer Kisoen Rahimbaks, his replacement Karyantika Nadimin, the commissioners Nanka, Riboed and Egbert Stanford and the secretary Sarjadie Sariman, known as Ponimen. In the Netherlands, ties have been maintained with families of the Santoe brothers and the Permauls.

Fear, abuse, greed and corruption

Sarjadie Sariman, born in Longmay on February 2, 1946, tells the heartbreaking story, “I started working on the plantation from the age of 15. I have been everything, pan boiler, an operator on heavy machines, all-rounder in the factory. The work on the plantation was harsh, dangerous, and degrading. The thatchers were only assigned task work. They paid for each ton of reed, cut, sorting, transporting and loading in pontoons, Sf 2.75 per ton. We went on strike just like the workers of Mariënburg, then also modern slaves, Sf. 3.75 per ton to be received. We protested the wages of Sf. 14.50 to Sf. 20.00 per week and working weeks from 77 to 168 hours. For a while, I worked at the boilers, about 144 hours a week.

Waterloo workers in front of Mohammed Ashiem’s shop. Picture courtesy Mr Donk.

“For years, the factory’s four steam boilers had been controlled by two workers, both of whom remained in the factory from 6:00 AM. Monday to the following Sunday morning. Nobody wanted to work near the steam boilers. One had already jumped. All four were so old and worn out that they were in constant danger of death there. I was able to take a nap at the factory for 1 to 2 hours at a time. This on a narrow wooden board. The boilers always had to be checked. Food and everything we needed had to be delivered to the factory. You could go home on Sunday to see the children and to sleep”.

He stated that “Sankar himself lived in great opulence in the Big House. The old plantation house with a hundred windows; of which a window is said to never open; out of respect for the governor of Suriname. I tell Ponimin that my father-in-law Bahadur Bipat once told me that Sankar’s wife, Zohorah, once said to him, “What in the world I can’t buy”. However, the gap between rich and poor on the plantation was like the deepest gap in the Grand Canyon. This was also noticed by the journalists who travelled to Nickerie to cover the chaos at Waterloo. Rudy de Bruin, Guno Meye, Sally.Blik, Leo Morpurgo, N. Haakstam, Omar Bradley, and Benny Ooft.”

Living Conditions and Strike

“In addition to Sankar’s house and a few new houses made of wood and stone, many shacks in which no pig would live, dark, musty, uncomfortable, open-air bathroom, plumbing toilets, open discharges. The home of the loose thatchers, the former hospital of the plantation, divided into four cells for four people, dark without lamps. On arrival, each cane grower gets four (ed: crocus) bags for his wooden bed, two for his mattress, there is plenty of grass, and two to sleep in and mosquito protection,”

Donk put this question to Ponimen – “Why do these people live and work here”?

He said, “It is difficult to answer. There was an unhealthy spirit on the plantation. The Waterloo management has abused a terrible weapon: Fear. Fear of the verbal abuse of Mrs Sankar, of whom everyone was afraid. Fear of the manager Mister Sama Chan, her brother and brother-in-law of Sankar. Fear of dismissal and deployment to the unknown outside world. The plantation was a state within a state. Fear of the return to Guyana, where there was no work (Guyanese workers). Taking advantage of the Javanese’s deep attachment to his family, his gentle disposition and his love for his familiar environment, however bad. Use has been made of the greed of senior officials, party bosses, who regularly visited the Big House and, like the inspectors, closed their eyes to abuses in the housing, water supply, wages, working hours and had no ear for complaints”.

It is alleged that Mrs Sankar was confident in their Legal Counsel Lachmon’s capacity to influence Government policy and enforcement action would protect her from any consequences. Their relationship, as mentioned before, goes back to Nickerie when he was their lawyer. The author claims that “Mrs Zohorah Sankar’s statement was that no union or worker will be able to change the existing situation as long as the Vathan Hitkari Party (V.H.P.) under the current leadership rules the country. In March 1972, Zohorah. Sankar denied these allegations. An advertisement by her appears in various newspapers. The March 8, 1972, daily newspaper Onze Tijd states: “Notice: We are very disappointed and annoyed that the Union can be so low as to make the very false statement that Mrs Sankar said, that we are under the protection of V.H.P. That is completely false. A.Sankar”.

Khan was not the Estate Manager at this time, but Sama Chan, the brother of Mrs Sankar. Mrs Sankar already fired Esau Khan in 1952.

It was March 25, 1972, when C47 called on the entire Surinamese nation to participate in the struggle to improve the destiny of working people in Suriname generally and in Waterloo in particular.

Film Paigham Inspired Labour Unrest

The plot in the 1959 released Bollywood movie motivated Waterloo workers to rise up and change the conditions under which they existed and improve the quality of their lives through militant action.

| Paigham’s plot:

The movie traces the lives of the family of a widowed lady, her two sons and daughter. Mrs Lal, a widowed lady lives with her two sons, Ram and Ratan, her unmarried daughter, Sheela; Ram’s wife, Parvati and her children. Ram works in a mill and Ratan is studying engineering in Calcutta. When Ratan returns, he is offered a job at the same mill, falls in love with a typist named Manju, much to chagrin of Malti, the daughter of the mill-owner, Sewakram. When Ratan finds out that Sewakram has been defrauding the mill employees, he decides to form a union, a move that is opposed by his brother Ram, who is devoted and loyal to Sewakram. Things go from bad to worse when the workers decide to go on strike, while Ram decides to throw Ratan out of the house. Word gets around that Ratan is against Sewakram, and soon he gets blacklisted. Sheela who was supposed to marry Kundan, the son of Sitaram, has her marriage cancelled, and the family lose their prestige and credit in the community. The question remains, will the workers continue to be at the mercy of Sewakram, and will the Lal family be re-united again and is answered during the latter half of the movie. The movie is available on YouTube with English subtitles (caption on) at this link Paigham |

Jusuf Ali Santoe would confirm that during Khan’s management of Waterloo, “Life on the plantation was pleasant.” The author interviewed Jusuf Ali Santoe. He was born on April 5, 1930, and is married to Mariam Santoe-Amir.

“Life on the plantation had a pleasant atmosphere. In fact, people were satisfied with very little. Not much was earned, but with very little money, one could get the basic items. Most people worked for about 20 cents an hour and earned between twelve and twenty guilders weekly. With this, they bought cooking oil, potatoes, salt, bloem (flour), etc. You could find fish on the plantation and in the surrounding area, while a vegetable garden provided vegetables. On certain holidays or on Sundays, football and cricket matches were organized on the plantation. They drew a lot of audience. People from Nieuw Nickerie and the surrounding polders came to enjoy themselves. At the Java parties, gala-long music was played. For a small contribution, you could then dance with the dancer. The gentlemen liked to do that, especially when their wife was not there. At the end of the year, Amir Sankar organized the so-called beggar-day, the day of the poor (beggars). Two bulls, sheep and goats were slaughtered. They cooked the meat at the Big House. The workers who lived on the plantation could eat to their heart’s content.”

He added, “Then there was enough rice, dhaal, pumpkin, boulanger (ed. eggplant)and meat. The men each received a jug of rum, and the women took home some sugar, which was the good times. Some say, therefore, that Sankar was not bad. But his wife had a sharp tongue. She was therefore feared, as was her brother Mr Chan. You shouldn’t be disgraced with her. It is said that Sankar did not care about the small increase, especially about them. The plantation was lost. “

Jusuf Ali Santoe pointed out that “Sankar had behaved as it was in colonial times. He bought not only the factory and the fields; but also the people and their children. He had taken on what the colonial government should have done. However flawed, he provided medical care, housing, light and water. What did the colonial government do to the plantation when Sankar left?

Santoe was balanced in his assessment of Waterloo history. And while he had some praises for Mr Amin Sankar, he asked, “What did the colonial government do to Mariënburg when it got its hands on the plantation? “Nothing,” says Ali. People were left to their own devices, especially on Waterloo. The plantation was plundered to the last stone under the watchful eye of the government and its representation in the district. A historical crime took place. Nobody intervened then.”

Mrs Z. Sankar, Her Brother Sama Chan, “Not a cent more.”

The author also interviewed Jusuf’s brother, Roshan Santoe, born August 9, 1942. He confirms Jusuf’s story but gives some additional information. “It was slave work on the plantation. Wages were very low, long working hours were worked, and overtime was not paid. Our parents were satisfied with a plate of rice, but the youth wanted justice, and more humanity. How could a feudal system survive the 1970s and the present? My father, Karamat Santoe, was a blacksmith on the plantation. He could perform miracles with blow bar and coal and iron. He had learned from the whites from England, the former plantation owners.

“Sankar loved my father. He could not imagine that we, the children of Karamat, stood up for a better life. We were not ungrateful but did not want to be slaves. The Paigam movie really opened our eyes. Aslam Santoe, Matto Santoe, Hoesmad Santoe and Sjako Santoe started fighting others. In 1961 Aslam, Matto and Hoesmad were fired. Although they grew up on the plantation, they had to leave the plantation. I too had to suffer the same fate. The battle was fierce. Mr Chan said, “Even if the plantation breaks, you won’t get a cent more.”

“Mrs Zohorah Sankar was not easy. Early in the morning, the managers of the plantation at the Sankar home received the work assignments. She also gave the assignments and instructions. I experienced myself that she just slapped one of the men because she was dissatisfied. Such things have been repeated many times. For us young people, the measure was full. “With a bleeding heart, many fighters have been forced to leave the plantation. I think the Sankar family also had to give up the plantation with great pain. Sankar had become a millionaire through the plantation. He was already old, he could not keep up with the times. That was decisive. The total destruction of the sugar plantation was ushered in.

In March 1969, the Union was strong under Mr Eddy. J. Bruma, not like in 2007 when “Money, politics and power largely replaced the fate of the workers. There is great controversy among unions and power stations, but it was different in the case of Waterloo. Union leaders fought with their lives at stake.”

The period from 1960 to 1970 witnessed significant labour unrest. December 7, 1953, and September 7, 1961, agreements raised conflicts. Workers wanted the “right to association,” which had been trampled upon, and they were “promised improvement.” After a new deal was signed, the owner of Waterloo again ignored all workers’ rights, according to Mr Donk. “The Rosheuvel commission was established by the Minister of Social Affairs E.M.L.Ensberg. They had to investigate the social conditions on the plantation. Indeed the conditions turned out to be very bad. On August 31, another strike broke out, which lasted until September 6, 1968. According to the Union, Mrs Sankar used every method from bribery to deportation, to scare the workers into compliance.

For the Guyanese workers, who mainly were cane cutters at the bottom of the ladder, Chan determined whether people could work in Suriname or not.” Her brother, Sama Chan, was at the centre of the conflict. Since his taking over the estate management, it was the beginning of the end of Waterloo.

Khan decided to keep his distance in not getting involved, especially that Sama Chan and Zohorah were ungrateful. He saw the end was near, and there was the hope of Waterloo being resurrected.

Ponimen tells me the following: “As early as December 1968, Sankar had tried to relieve five of us from the plantation’s homes with a court order. It involved me, Ajaub Khan, Zafdar Ali, Jackey Permaul and Lokia.

“In May 1969, the verdict fell to our disadvantage. The government then urged us to vacate the houses before 8.00 AM on Tuesday, May 27 1969.” The very children of the plantation and now grown men, agitated by the Hindustani film, “Paigham, the Message”, were evicted, the same way that Khan was evicted from his home. Khan fled to Paramaribo to join his second wife. And eventually, Amin and Ahmad Sanakar’s grand mansions on Main and Camp Street, Georgetown, crumbled. Amin’s daughter Lyla Kissoon pulled the house down and built a new one. The siblings of Amin became divided over the inheritance their mother left.