Friday October 30th 2009, will mark the 125th anniversary of what historians describe as perhaps the bloodiest massacre in Trinidad and Tobago under British rule. On October 30th 1884, 22 Indians were killed and 120 others injured in a hail of police gunfire at two Hosay processions in San Fernando. Included in the casualties were defenceless women and children.

All took part in the procession

Many historians who have studied the event reveal that Hindus as well as Africans were part of the Indian and muslim-based street processions. Historians also believe that never before had such a large, armed military force assembled in colonial Trinidad, or in any other West Indian colony, at any cultural event.

Many historians who have studied the event reveal that Hindus as well as Africans were part of the Indian and muslim-based street processions. Historians also believe that never before had such a large, armed military force assembled in colonial Trinidad, or in any other West Indian colony, at any cultural event.

Hosay is the commemoration of the death of the two soldier-grandsons of Prophet Mohammed who were killed in war in Iraq in 680 AD. The centerpiece of Hosay is the procession of taziyas made of cardboard and tinsel. They are symbols of the tomb erected over the remains of Husain, one of the two grandsons, in the plains of Karbala. Hosay is celebrated annually in Cedros and St. James in Trinidad. It has been banned by law in Guyana. In Jamaica, it is the second largest national cultural event. Hosay is not a festival, and it is not to be viewed or described as Indian Carnival.

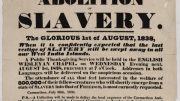

In 1884, the government banned Hosay processions from entering the towns of Port of Spain and San Fernando. This was tantamount to killing the best part of the parade. An Indian by the name of Sookoo, and 31 others, drew up a petition to the governor which was rejected. Sookoo felt that the law was unjust and discriminatory, and consequently decided to defy the regulation with an act of civil disobedience.

In the 1884 Hosay, each estate had its own taziya, accompained by tassa drummers and stick fighters. There were processions from Wellington, Picton, Lennon, Rowbotton, Retrench, Estate, and Union Hall Estate. Other processions came from Ne Plus Ultra, Corinth, Palmyra and St Madeline estate. It was a dramatic parade, attracting huge crowds of spectators annually in San Fernando.

Police detachments were strategically deployed with cartridges loaded with buckshots to scatter-shoot into the crowd. A contingent of 74 policemen was headed by Captain Baker at Mon Repos Junction. Twenty soldiers arrived by special train from Port of Spain. Twenty-one British marines were sent to Princes Town to reinforce the police. The British warship, H.M.S. Dido, rushed down from Barbados to anchor in waiting outside the San Fernando harbour.

Armed forces were placed at the three main entrances leading to San Fernando. They were posted at the Les Efforts junction, which was a toll gate that lay at the junction of Cipero Street and Rushworth Street. At this point, 34 armed men, 20 soldiers and 14 policemen were stationed. The other entrance was at the point where Royal Road met Mon Repos Estate. The next (northern) entrance was where Point-a-Pierre Road formed a junction with Mount Moriah Road. Through this entrance, crowds surged from estates like Vista Bella, Marabella, Concord, Bon Accord, and Plein Palais.

Few Indians believed that the police would shoot them down in cold blood. After all, they were simply participating in a customary religious procession. One survivor said that he did not believe that the police would “shoot people like fowls.”

The massacre took place on a Thursday. On horseback, Magistrate Arthur Child read The Riot Act amid the thunder of tassa drumming, chanting, singing, and stick-fighting. Few Indians could have really heard what was being read. Even if they had heard, few could have understood English at that time. Child ordered the police to shoot at the procession at Les Efforts. Two volleys were fired into the crowd, followed by some sporadic shooting. Those in the front of the procession were mowed down by a hail of bullets. Taziyas fell to the ground. The dead and wounded lay in pools of blood in the street. There was shock and panic. There were shrieks of terror and cries of pain. Some ran into the canefields. Others scampered for shelter from the bullets.

At the Mon Repos junction, the stipendiary magistrate read the Riot Act. Shots were again fired. Again, tazyias fell to the ground, and men, women and children lay dead. The processions on the Point-a-Pierre Road were speared gunfire because they were persuaded to turn back. The nation was shocked into disbelief.

The number of Hosay participants who were killed on October 30th 1884 varies in different accounts. Historian Kelvin Singh concludes that 150 were wounded in the massacre. Those who were fatally wounded ran into the sugarcane fields where they were found afterwards. Others died weeks and months later at home and in the hospital. A reasonable estimate to make is that 22 Indians were killed and 120 injured.

Sadly, the events surrounding this significant day in the history of Trinidad are known only by a few. October 30th 1884 has been overlooked in many of the texts that chronicle the nation’s experiences during colonization. The courage of these jahajis [indentured immigrants] martyrs who fought and gave their lives for the freedom to worship must not be forgotten. The fact that Hosay survives to this day is testimony that the spirit of these martyrs continues to live.

———————————————————————————

CREDITS:

– Story by Dr Kumar Mahabir. Assistant Professor

School for Studies in Learning, Cognition and Education

University of Trinidad and Tobago (UTT)

Be the first to comment on "The Muharram Massacre in Trinidad and Tobago"