Critically Unpacking Indian Arrival Day: Why Celebrating Indian Arrival Day is Problematic?

Today is always a difficult day for me, it is Indian Arrival Day.

This day is marked as May 30th in Trinidad and May 5th in Guyana among other countries indentured labourers 1 were violently displaced to by white colonizers.

Indentured Muslim from Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh, India

On Indian Arrival Day Instead of Celebrating, I Choose to Remember and Reflect

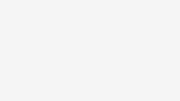

Celebrating Indian Arrival Day is so problematic so today I do not celebrate my ancestors ‘arrival’ in the Caribbean INSTEAD I remember and am mindful of the pain as well as trauma my ancestors endured as indentured labourers in the horrendous conditions on the plantations due to British colonization.

I am mindful of the intergenerational trauma I carry due to this colonial displacement and the constant unlearning of colonial harm as well as decolonization I must engage in.

Within that same pain, I also remember the collective strength and resistance our ancestors displayed in the Hosay Massacre in Trinidad and the Muslim-led rebellion that followed with the white colonizers’ response of the Rose Hall Massacre in Guyana 5

I especially remember the strength and resistance displayed by women who fought against colonial oppression, patriarchy and misogyny. Through their strength and resistance, I realize, I am the strength of the past women who have walked before me. My ancestors, with each act of their resistance against colonization, energy, and hope awakens inside me.

These powerful women who survived, thrived, and endured so many hardships under colonization are my source of strength and make me who I am today. To know that this strength and resistance lies within my blood allows me to know I can overcome future hardships. In that same remembrance of those who resisted colonialism, I also reflect on how I can continue my journey of resistance, unlearning colonial harm and decolonizing.

Remembrance and Reflection: Pain, Trauma, Displacement, Tracing Ancestry, and Homeland

Indian Arrival Day for me personally is a day I can not help but reflect on the pain and trauma my ancestors endured being ripped away from their homeland, never to see Hindostan’s shores ever again due to British colonization. I remember the day I went to the archives in Trinidad and Guyana. I remember the feeling flipping through old cracked books with pages missing, broken, and illegible, praying in my mind thinking InshaAllah (God willing) I find my ancestors’ Emigration Passes. SubhanAllah (Glory to God), I was able to obtain two but was not able to obtain others on those trips. I remember learning how the colonial evil of indentureship separated two brothers from each other, separated a mother from her child and husband, never to see each other again, or have their families see each other again. I remember the feeling the first time my eyes laid on my ancestors’ names, the villages they came from, and touching the Emigration Passes. It was as if the holes in my collective intergenerational memory were slowly filling little by little. Internally I wanted to collapse and cry uncontrollably as an emotional release since my entire life was waiting for that moment (the next moment I’m waiting for is physically stepping foot on Indian soil). To this day I have those Emigration Passes on the wall next to my bed as a constant reminder, as the last thing I see before I go to bed and the first thing I see when I wake up so I will never forget.

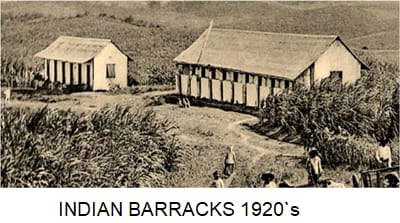

Indentured Labourers in front of their thatched-roof huts

This Indian Arrival Day, I remember with pain since the day my ancestors were displaced that I may never be able to go to India, where my ancestors I traced so far are from. I may never be able to walk on those same shores of my homeland again or have my feet step on my ancestral soil or know how the land would feel under my feet. I may never know how it would feel the first moment my eyes lay on its shores or know the smell of the natural sweet musk of my homeland. I may never see the houses and lands my ancestors previously lived on. I may never know how it feels to have my forehead touch the ground of my homeland in sujood 6 while performing namaz 7 in my ancestral village masjid. The masjid my ancestors have gone to for generations before they were deceived and ripped from their homelands, displaced as indentured labourers in the Caribbean. I may never know how it would feel to hear the adhan 8 or go to jummah 9, or hear the khutba 10 in my native tongue, in my native land in my ancestral families masjid.

It pains me that I am separated from my family in India, that I will never know how it would feel to meet the descendants of all my ancestors who had their family ties severed due to British colonization under indentureship. It pains me that I will never be able to give them a hug and get to know them knowing there is shared blood running through our veins. This has been a dream of mine ever since I could remember myself.

It especially pains me that I do not know if my family is safe or still alive in India and what they are enduring with ongoing Anti-Muslim violence under the Hindutva ideology of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s Hindu supremacist government.

Unfortunately, this same Hindu supremacist, Hindutva ideology, and Anti-Muslim racism is present in the Indentured Diaspora (among the descendants of indentured labourers) and Indo-Caribbean spaces as well. My pain and fear about my family’s safety have only increased in the past few months with the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) 11 gaining assent on December 12th, 2019, coupled with the National Register of Citizens (NRC) 12, which has led to violent policing of protesters who oppose these anti-Muslim policies. Many of these violent police responses to protesters occurred in Uttar Pradesh 13 (such as at Aligarh Muslim University- AMU), where a majority of indentured labourer’s ancestors can be traced to and the majority of violence was directed at Muslims. The proposed nationwide NRC and CAA policies together 14, leave the citizenship of India’s 200 million Muslims (who form 14% 15 of the population) across multiple generations questioned and will render them stateless refugees in detention centers and concentration camps across the country. 16.

This Anti-Muslim violence eventually culminated in the Delhi 2020 17genocide, with violence, as well as oppression, continuing to occur towards Muslims who are used as scapegoats and blamed for COVID-19 18.

This Anti-Muslim violence eventually culminated in the Delhi 2020 17genocide, with violence, as well as oppression, continuing to occur towards Muslims who are used as scapegoats and blamed for COVID-19 18.

Within this context, since I know the areas where some of my ancestors originated from, I am constantly looking online for updates to piece together what is happening and how they may be affected. This leaves me fearful if my family was harmed during the various protests; if in their rural villages they have access to the documents required under the NRC, if their citizenship will be stripped or worse if they will be sent to the detention camps and what their experiences are with COVID-19. This Ramadan I find myself raising my hands making dua19 for the safety of this family I have never met, yet I have love for India. As I make dua I realize even though I do not know who my exact family are in India, Allah knows exactly who each of my family members are and is watching over them which gives me some sense of comfort.

The reason I keep saying I may not be able to go to the homeland of my ancestors I traced in India is due to its anti-Muslim political context and government. Muslims who resided in India for generations are having their citizenship stripped from them, much less the chances of a Muslim descendant of indentured labourers displaced for generations before partition to successfully obtain an Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) Card. Or even a Visa to enter India for that matter, since when applying the religion of parents and grandparents are collected, which is concerning if you are a Muslim (especially if all these family members are Muslim as well or if you have what is deemed a ‘Muslim sounding name’).

Muslims are constantly policed, viewed as a security threat, and viewed as ‘foreign’ to India under Hindutva and Hindu supremacist rhetoric, which influences OCI and Visa application decisions. On the other hand, the positionality of Hindu descendants of indentured labourers (especially those who (and their family) have what is deemed ‘Hindu sounding names’) includes not needing to worry about being rejected to enter India if they wish to reconnect with family or visit their ancestral villages on the basis of their religion.

Hindu Indo-Caribbeans (and Hindus in other indentured diasporas) have the power/ privilege of greater accessibility 20 to enter India’s borders and move about without needing to be cautious of Anti-Muslim rhetoric as well as violence. This reality is a lot to take in knowing my Muslim identity can become a barrier to me physically entering India, visiting my family, and stepping foot in my ancestral villages. Because to be Muslim in Indian spaces is to be viewed as a ‘foreign’, dangerous security threat.

As the descendant of Muslim indentured labourers (Indo-Caribbean) hailing from regions affected by the CAA as well as the proposed India-wide NRC, although I am heartbroken over the treatment of Muslims in India, although I have an emotional response to these Anti-Muslim policies and accessibility issues to entering India to go to my ancestral village as well as to see my family, I must also acknowledge my power/ privilege at this moment. It is not to say that the trauma of indentureship during colonization is a privilege (it is not), it is the reason for me and my ancestors being separated from our family in India. But the reality is that now as the descendant of those who experienced indentureship I have accumulated power and privilege over time in regards to my citizenship.

My family has power/ privilege due to their citizenship in countries indentured labourers were displaced to such as Trinidad and Guyana. Due to a second migration, I have citizenship in Canada (as well as my family), in relation to the precarious, violent and deadly lived experiences of Muslims in India regarding citizenship, thus giving me power/ privilege. I am privileged because I do not have the lived experience of being in India during various genocides against Muslims or experiences with the violence surrounding the CAA as well as NRC and my direct relatives are not affected. Although I have lived experiences being oppressed and marginalized with Hindu purity politics including Hindutva ideology, Hindu supremacy, and Anti-Muslim racism in various spaces (such as Indian, Indentured diasporic, and Indo-Caribbean contexts), I still have privilege since I am not experiencing the violence within the context of India. The reality is that with each breath I take here knowing the security, power, and privilege I possess due to my citizenship, my family in India are being questioned of their citizenship and having to prove theirs.

My family has power/ privilege due to their citizenship in countries indentured labourers were displaced to such as Trinidad and Guyana. Due to a second migration, I have citizenship in Canada (as well as my family), in relation to the precarious, violent and deadly lived experiences of Muslims in India regarding citizenship, thus giving me power/ privilege. I am privileged because I do not have the lived experience of being in India during various genocides against Muslims or experiences with the violence surrounding the CAA as well as NRC and my direct relatives are not affected. Although I have lived experiences being oppressed and marginalized with Hindu purity politics including Hindutva ideology, Hindu supremacy, and Anti-Muslim racism in various spaces (such as Indian, Indentured diasporic, and Indo-Caribbean contexts), I still have privilege since I am not experiencing the violence within the context of India. The reality is that with each breath I take here knowing the security, power, and privilege I possess due to my citizenship, my family in India are being questioned of their citizenship and having to prove theirs.

As long as I can remember I have always had a strong connection to my South Asian (and Indian) heritage and identity growing up. I view South Asia as my homeland especially present-day India, where I have already traced some ancestors to. I say South Asia since “indentured labourers left the territory known as Hindostan colonized by the British Raj that lies in present-day India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal among other countries that are termed South Asia collectively. Therefore the displaced indentured labourers did not solely come from the present-day country India (a majority did) but some came from other countries in South Asia” and I may have ancestry in locations other than India (Rahman 2018, 267 21).

Although there are criticisms surrounding the problematic nature of the term South Asia (and South Asian), since I do not know the locations of my ancestral roots, South Asia becomes a point of reference I can use that encompasses all the possibilities of my ancestry without having to single out India solely. South Asia (and India) is not something in my past my ancestors left solely linked to history that ends the moment they boarded those ships, instead it is a place that dwells in my heart in my present. Each time I practice and remember my culture and my religion, I view it as an act of resistance against the colonization my ancestors endured. I WILL NOT FORGET!!

Remembrance and Reflection on Resistance

On Indian Arrival Day, I reflect on how every time my ancestors practiced their culture or religion it was an act of resistance against colonization. Every time this was passed down, every time my parents (and family) taught me something about my ancestry, my culture, or my religion and every time I practiced what I learned, I view it as MY act of resistance against colonization. Every time I go to Trinidad and Guyana I always make it a point to visit my family’s masjids 22 built by my ancestors and I pray jummah 9 there. Every time I do so I feel so grounded in knowing the sacrifice and resistance my ancestors made in order for me to practice my South Asian, Indian, and Indo-Caribbean culture as well as Islam and to call myself Muslim today.

Every time my forehead touches the ground in sujood while performing namaz, I am touching the ground my ancestors toiled. The land they used their small earnings to save bricks, one by one, to build the humble place of worship I can now enter and feel their love and presence in. This is felt while hearing my family deliver the khutba in a sweet familiar Trinidadian or Guyanese accent that fills my heart with joy. When I do this I am actively resisting colonialism and honouring the legacy of my ancestors. Every time I hear qaseedas 23 sung they remind me of home, my parents, especially my mother who won qaseeda singing contests when she was younger and my family.

When I say home it reminds me of all the places I feel a deep connection with including South Asia, India as well as the Caribbean, specifically Trinidad and Guyana. One qaseeda that was known as my mother’s signature song, that she was popularly known for singing in family and religious gatherings is Lap Pe Aati Hai Dua. One line in this qaseeda that always stood out to me was Ho mere dam se yunhi mere watan ki zeenat, which loosely translates to may my homeland through me attain elegance. This line always makes me think of my ancestors and my homeland South Asia (and India).

When I say home it reminds me of all the places I feel a deep connection with including South Asia, India as well as the Caribbean, specifically Trinidad and Guyana. One qaseeda that was known as my mother’s signature song, that she was popularly known for singing in family and religious gatherings is Lap Pe Aati Hai Dua. One line in this qaseeda that always stood out to me was Ho mere dam se yunhi mere watan ki zeenat, which loosely translates to may my homeland through me attain elegance. This line always makes me think of my ancestors and my homeland South Asia (and India).

With each word of qaseedas sung melodiously in Urdu I am actively resisting colonialism and honouring the legacy of my ancestors. Every time I hear the rich, sweet sing-song Trinidadian and Guyanese accent I view as my first language, every time I ask my nanni 24 about her childhood or our history and receive gifts of knowledge or every time I learn another family recipe I am actively resisting colonialism and honouring the legacy of my ancestors. Every time I wear my shalwar kameez and orhni 25 on the way to the masjid, every time I smell the sweet scent of agarbatti 26 or attar 27, every time I attend a Moulood/Qur’an Sharif 28 function, every time I keep roza 29, every time I pray salaat in jamaat 30, every time I hear my father say his niyyah 31 in Urdu before performing namaz, every time I hear the tazeem ‘ya nabi salaam alaika, ya rasul salaam alaika, ya habib salaam alaika…’, I am actively resisting colonialism and honouring the legacy of my ancestors.

These acts of resistance against colonization are a way of celebrating my South Asian-ness, Indian-ness, Indo-Caribbean-ness (Indo-Trinidadian-ness and Indo-Guyanese-ness), Caribbean-ness, Muslim-ness while acknowledging my ancestors’ experience of indentureship. This is because I view the fact that I am Indo-Caribbean and Muslim as being intrinsically linked to my expression of South Asian-ness/ Indian-ness and visa versa, where my South Asian-ness/ Indian-ness is intrinsically linked to my Muslim-ness and Indo-Caribbean-ness. These identities are not a dichotomy where I must choose one or the other.

When I self-identify as South Asian (Indian), I should not have to choose between Indo-Caribbean or South Asian (Indian), where I can not be both. The same goes for when I self-identify as Muslim, I should not have to choose between Muslim and Indo-Caribbean (or Indian), where I can not be both. These identities are not a dichotomy as well where I must choose one or the other. My loyalty is not lessened in all these spaces or identities but is strengthened collectively. By simultaneously identifying as South Asian (Indian), Indo-Caribbean, and Muslim my authenticity to claims of South Asian-ness (Indian-ness) or Indo-Caribbean-ness should not be questioned, it is problematic and oppressive to do so.

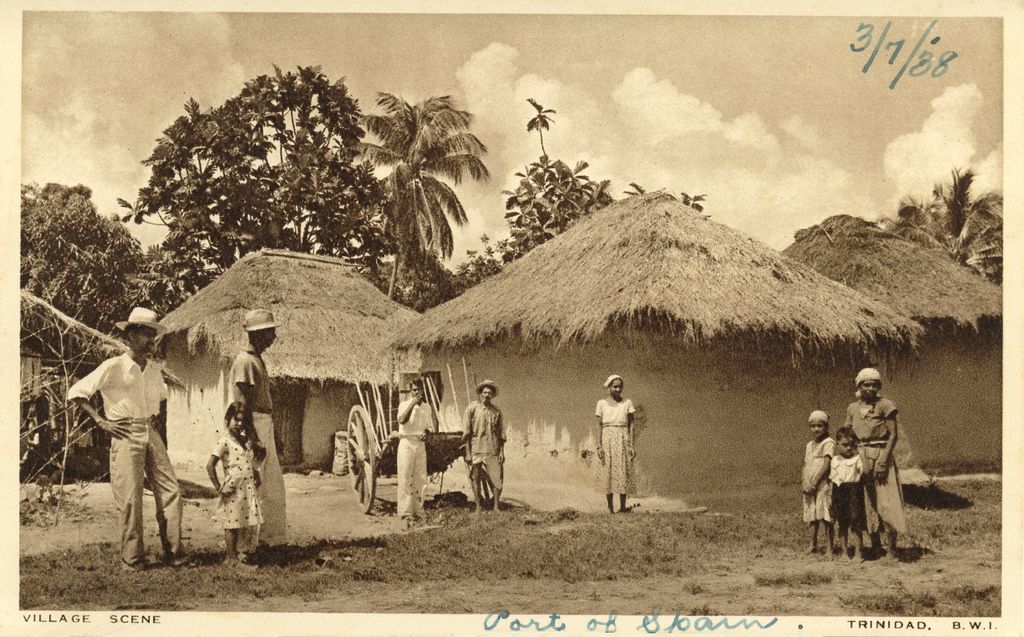

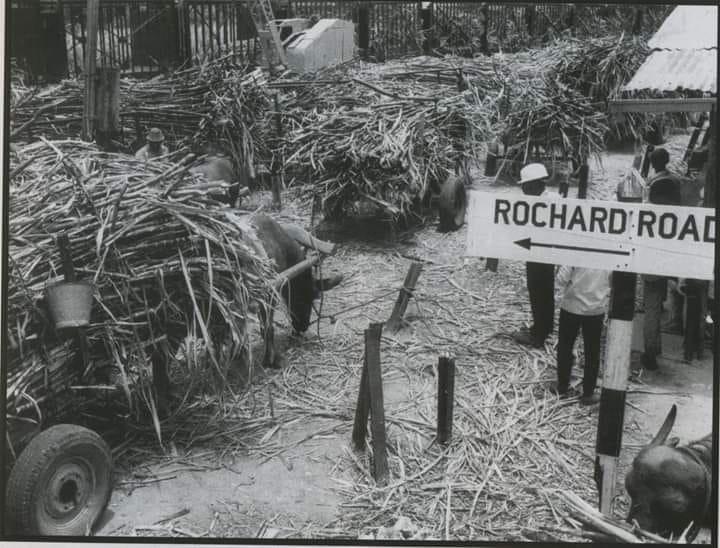

Sugarcane being brought for sale

This is my personal journey of self-identification and I know many other Indo-Caribbeans have different experiences with self-identification based on their intersectional positionalities as well as lived experiences. Each of our journeys is valid and no one’s journey should be belittled. Yet, I am constantly reminded in Indo-Caribbean spaces that my identification as a South Asian (and Indian) and viewing South Asia (and India) as my homeland is not welcome. It is looked down upon condescendingly by Indo-Caribbeans who do not identify with South Asian (and Indian) or do not view South Asia (and India) as their homeland and instead view the Caribbean as their homeland. These Indo-Caribbeans act as gatekeepers to Indo-Caribbean-ness, playing purity/authenticity politics in relation to giving more validity to expressions of Indo-Caribbean-ness based on higher degrees of Caribbean identification rather than South Asian/ Indian identification in Indo-Caribbean expressions. This is done while simultaneously being critical of purity/ authenticity politics in other spaces, which is hypocritical.

Self-identifying as South Asian (and Indian) or viewing South Asia (and India) as your homeland does not make you more or less Indo-Caribbean. The same goes for self-identifying as only Indo-Caribbean (and Caribbean) and viewing the Caribbean as your homeland does not make you more or less Indo-Caribbean.

Rejecting my self-identification reflects the stereotypes others wish to perpetuate by boxing me (and others who self-identify similarly) into what they think an identity should be rather than accepting intersectional differences in lived experiences based on positionality that influences self-identification. Many of these Indo-Caribbeans think I am naïve to look towards South Asia (India) as a homeland that I must be misinformed, not cognizant of my history, or simply passively relying on nostalgia as the reason to affiliate with South Asia (and India). This could not be further from the truth. To think of South Asia (or India) as a homeland is not to be naïve, passive, or uncritical towards South Asia (or India), one can be simultaneously feeling an affinity with that location and also deeply critical of it. It is because I am cognizant of my history as coming from a long line of ancestors who endured the trauma of indentureship, who resisted against colonization for so many generations, from whom I draw my strength from including from my grandparents/parents so I may self-identify as South Asian, Indian and Indo-Caribbean today. My parents and my childhood growing up have shaped these choices of self-identification profoundly. I am constantly honouring the legacy of my ancestors, my grandparents, and parents who came before me as a way of celebrating my South Asian-ness, Indian-ness, Muslim-ness, Indo-Caribbean-ness, Caribean-ness, Trinidadian-ness and Guyanese-ness.

Reflection on the Indian Arrival Day Connection to South Asian Heritage Month

On Indian Arrival Day I also painfully reflect on how in Ontario May is South Asian Heritage Month and May 5th is South Asian Arrival Day due to The South Asian Heritage Act, 2001 (originally Bill 98) 32. Similar to identity purity/ authenticity politics expressed earlier, Indo-Caribbeans are marginalized, invisibilized in South Asian spaces by Mainland South Asians/ Indians.

I coined the term Mainland South Asians/ Indians 33 “to refer to those from the subcontinent consisting of India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal and other countries collectively known as South Asia” who either live in these countries or migrated after partition (1947) (Rahman 2018, 268). Indo-Caribbeans are usually left out of South Asian (and Indian) spaces and invisibilized because Mainland South Asians/ Indians act as the gatekeeper of South Asian-ness (and Indian-ness) denying Indo-Caribbeans from claiming South Asian-ness (and Indian-ness) or entering these spaces due to the belief that Indo-Caribbean culture is an impure or bastardized version (Rahman 2018, 264, 284). This is so problematic!!! Especially since there would be no South Asian Heritage Month without the Indo-Caribbean community, who can be attributed to its existence, by advocating, using grassroots mobilization and lobbying for an inclusive celebration of South Asian culture in the South Asian Heritage Act, 2001 (Rahman 2018, 281).

South Asian Heritage Month originated from Indian Arrival Day celebrations by Indo-Caribbean organizations like the Ontario Society for Services to Indo-Caribbean Canadians (OSSICC) and the Indo Trinidadian Canadian Association (ITCA) (Rahman 2018, 281). This eventually evolved into Indian Arrival and Heritage Day, then Indo-Caribbean Heritage Day, and then Indian Heritage Month before South Asian Heritage Month was established. South Asian Arrival Day in Canada is May 5th because it is Indian Arrival in Guyana on May 5th. May 5th is used because indentured labourers displaced to Guyana in 1838 are believed to be one of the first South Asians in the Americas.

As problematic as Indian Arrival Day celebrations are, there is frustration in being the most marginalized, invisibilized, denied as well as forgotten in the representation of South Asian Heritage Month expressions, events, and celebrations that Indo-Caribbeans advocated so vigorously for. This is due to the inequity between Mainland South Asians/ Indians and Indo-Caribbeans since Mainland South Asians/ Indians have more power/privilege to claim South Asian-ness (and Indian-ness) than Indo-Caribbeans.“This left the visual representation and memory of this month as solely Mainland South Asian/ Indian with few people knowing of this month’s Indo-Caribbean origins” (Rahman 2018, 281).

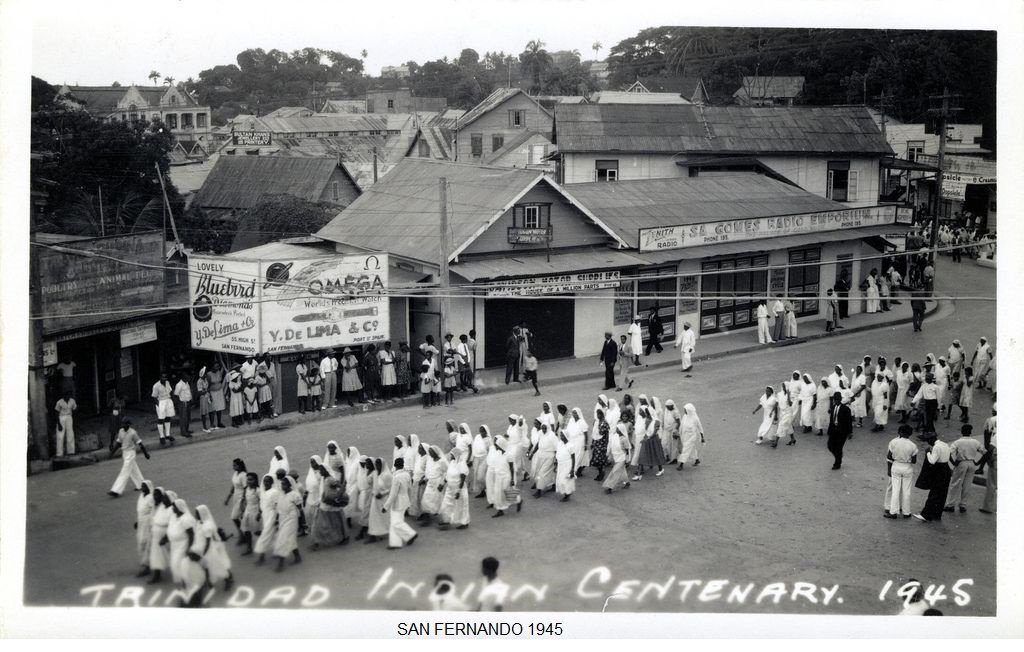

First generation Muslims in Trinidad

This exploitation of Indo-Caribbean mobilization for South Asian Heritage Month by Mainland South Asian/ Indians is an expression of colonial extraction. The colonial extraction of the emotional labour of Indo-Caribbeans by Mainland South Asian/ Indians for their gain and profit without even citing or acknowledging Indo-Caribbeans as the developers and reason this month was established.

If you are a Mainland South Asian/ Indian organization, blog, magazine, influencer, etc. that recently celebrated, wrote about, posted, etc. or will do so in the future about South Asian Heritage Month and did not cite or acknowledge its Indo-Caribbean origins or represent Indo-Caribbeans you are participating in reproducing colonialism. This act engages in the erasure of Indo-Caribbean voices.

If you are Mainland South Asian/ Indian be self-reflexive of your privileged positionality and use your power/ privilege to center intersectional marginalized or invisibilized voices, identities, and lived experiences. Use your power/ privilege as a Mainland South Asian/ Indian to share this knowledge with as many people as possible since so much of our history as Indo-Caribbeans was erased in these spaces. There are so few Mainland South Asian/ Indians doing the work of holding themselves accountable, who work in solidarity with Indo-Caribbeans without tokenizing them and who bring about actual structural change. We need to uphold each other, hold space for each other in our journey of decolonization, unlearning, and resisting colonial legacies of exploitation. These same criticisms apply to Mainland South Asians (especially Indians), Indentured Diasporas and Indo-Caribbeans in regards to Muslim representation, erasure and voices.

The Indian Arrival Day for this year (May 30th, 2020) will mark 175 years since 1845, which was the year the first ship docked with the first set of indentured labourers aboard in Trinidad. This means that many will be celebrating this day uncritically. It is important to continue having these critical discussions surrounding the colonial history of Indian Arrival Day so we can continue our journey of decolonization by unlearning colonial harm and resisting this violent history and intergenerational trauma.

- My intersectional positionality includes [but is not limited to] self-identifying as South Asian, Indian, Muslim, the descendant of Musalman (Muslim) indentured labourers from Hindostan, Indo-Caribbean, Trinidadian (Indo-Trinidadian), Guyanese (Indo-Guyanese), Caribbean and being born in Canada [with Canadian citizenship and a Canadian passport]. Definitions included in this article were originally published in my previous CaribbeanMuslims.com article The Trauma of Indentureship, Colonization and Resistance: Muslim Indentured Labourers in Trinidad and Guyana[↩]

- It is imperative to disclaim that Indentured Labourers and their descendants are not a homogenous community but composed of many intersectional identities with varying positionalities and social locations [with a wide gamut of various connections to South Asia/ India and some may have no connection to South Asia/ India]. [↩]

- Hindostan, n.p. Persian Hindūstan, and the Latin ‘India’, are both derived from the old-Persian term ‘Hindu’. Hindu is Persian for Sindhu, the name for the Indus River in ancient Sanskrit. Thus, ‘Hindustan’ is ‘the land beyond the Indus’. Hindustan became a commonly used term to refer to the Mughal Empire, comprising primarily of north India, prior to British rule. However, with time and colonization, the term widened its geographical scope to include the entire territory of British-ruled India. Hindostan can be defined as the “territory colonized by the British Raj (pre-partition India) that lies in present-day South Asia (India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Maldives (and at times Myanmar)” (Rahman 2018, 267-268). This is taken from my book chapter Indo-Caribbean Identity Formation in Canada: Challenges of South Asian/Indian Authenticity published in 2018 in the book Dynamics of Caribbean Diaspora Engagement: People, Policy, Practice, edited by George K. Danns, Ivelaw Lloyd Griffith and Fitzgerald Yaw[↩]

- past histories that echo through time to influence the present[↩]

- For further reading please refer to the 2009 article 170th Anniversary of the arrival of the first Hindustani Muslims from India to British Guiana in the Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, written by Bibi H. Khanam and Raymond Chickrie. Refer to the 2002 article The Afghan Muslims of Guyana and Suriname in the Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, written by Raymond Chickrie for more information.[↩]

- the act of low bowing or prostration to God towards the direction of the Kaaba at Mecca[↩]

- Namaz is a Persian word used among the speakers of Persian, Turkish and among the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent for the Islamic prayer known as Salah/Salat in Arabic. Namaz literally means ‘prostration’ and is used to mean ‘prayer’.[↩]

- The adhan, also written as adhaan, azan, azaan, or athan, also called ezan in Turkish, is the Islamic call to prayer, recited by the muezzin at prescribed times of the day. The root of the word is ʾadhina meaning “to listen, to hear, be informed about”[↩]

- Friday noon congregational prayer[↩][↩]

- a sermon preached in a mosque at the time of the Friday noon prayer[↩]

- The CAA amends the Citizenship Act of 1955, so that naturalized Indian citizenship can be granted to migrants from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh who are of Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi and Christian backgrounds. This option is NOT extended to Muslims. The CAA goes directly against Article 14 of the Indian Constitution by not providing the fundamental right of equality under the law, thus being illegal, undemocratic, against secularism, and unconstitutional. If the CAA was created under humanitarian reasons like what the BJP is suggesting then other minorities persecuted in surrounding countries should be included like Tamils from Sri Lanka, Buddhists from Tibet, Hindus from Bhutan, Christians from Nepal, Rohingya Hindus from Myanmar to name a few. (These arguments have been popularly cited in multiple sources, one source is The Conversation article India’s new citizenship act legalizes a Hindu nation by Anil Varughese[↩]

- The NRC calls for the register of all Indian citizens to be implemented across India by 2021, where each individual must prove Indian citizenship with ancestry documents. Assam has undergone this from 2013-2014. This process will be incredibly difficult, especially in rural areas where record-keeping is more minimal, for migrants and for those who do not have birth certificates or other official documents. (These arguments have been popularly cited in multiple sources, one source is the Human Rights Watch article “Shoot the Traitors” Discrimination Against Muslims under India’s New Citizenship Policy[↩]

- These arguments have been popularly cited in multiple sources, some sources are the Human Rights Watch article “Shoot the Traitors”Discrimination Against Muslims under India’s New Citizenship Policy and The Wire article More Brutal Than Even Jamia’: AMU Fact Finding Report Accuses UP Police of Violence, Islamophobia[↩]

- What cements the proposed CAA as being anti-Muslim is when coupled with the NRC. For example, the final updated Assam citizenship register left nearly 2 million people off the list with many living there for generations. A majority of those stripped of citizenship were Bengali Muslims, but those remaining who were stripped of their citizenship and who were also not Muslim can now rely on the CAA. The CAA allows those not on the NRC to still obtain naturalized Indian citizenship since they are not Muslim and ONLY Muslims are restricted from obtaining citizenship under the CAA. (These arguments have been popularly cited in multiple sources, some sources are The Guardian article India: almost 2m people left off Assam register of citizens and Human Rights Watch article “Shoot the Traitors”Discrimination Against Muslims under India’s New Citizenship Policy[↩]

- Muslims accounting for 14% or 200 million was mentioned in Soumya Shankar’s article India’s citizenship law, in tandem with national registry, could make BJP’s discriminatory targeting of Muslims easier.[↩]

- Those who do not make the NRC list and are Muslim will be sent to detention centers and concentrations camps, which are already under construction in Assam as well as other parts of India such as Punjab, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, New Delhi, and West Bengal. Under this planned genocide (such as the ongoing genocide in Assam) many migrants who were stripped of their citizenship are the ones forced to construct the massive detention centers that will house them. (These arguments have been popularly cited in multiple sources, some sources are Bibhudatta Pradhan’s article Millions in India Could End Up in Modi’s New Detention Camps and the DW article India builds detention camps for Assam ‘foreigners’ . It is important to note that this is all occurring within the context of an ongoing genocide in Kashmir. The research of Binish Ahmed in The Conversation article Call the crime in Kashmir by its name: Ongoing genocide furthers our understanding of the ongoing genocide in Kashmir as settler colonization as well as settler-occupation by the Indian state on the Indigenous Kashmiri peoples and their land.[↩]

- This argument has been popularly cited in multiple sources, one source is Shiv Sahay Singh’s article Delhi violence was a planned genocide, says Mamata Banerjee[↩]

- This argument has been popularly cited in multiple sources, one source is Aniruddha Ghosal, Sheikh Saaliq and Emily Schmall’s article Indian Muslims face stigma, blame for surge in infections [↩]

- dua, literally meaning invocation, is an act of supplication. The term is derived from an Arabic word meaning to ‘call out’ or to ‘summon’, and Muslims regard this as a profound act of worship. This is when Muslims connect with God and ask him for forgiveness and favors.[↩]

- I am referring to greater accessibility in regards to entry into India when one has the financial means to travel there. I acknowledge (and note) that there are socio-economic and financial access barriers among others to get to the point of privilege of being able to make the financial decision to take a trip to India. I acknowledge (and note) that there are other intersectional identities and positionalities that will have various ranges of accessibility to enter India (and have the financial means to travel there), which are not issues limited to solely Muslims. But due to the current political context in India Muslims face the brunt of this policing, being viewed as a security threat and ‘foreign’ to India under Hindutva and Hindu supremacist rhetoric.[↩]

- This is taken from my book chapter Indo-Caribbean Identity Formation in Canada: Challenges of South Asian/Indian Authenticity published in 2018 in the book Dynamics of Caribbean Diaspora Engagement: People, Policy, Practice, edited by George K. Danns, Ivelaw Lloyd Griffith and Fitzgerald Yaw.[↩]

- Places of worship, mosque[↩]

- Religious songs of praise sung by Muslims – which continues to be popular in South Asia as well as the diasporas[↩]

- maternal grandmother[↩]

- a scarf worn around the head or neck or shoulders by women for modesty, warmth or decoration[↩]

- Incense sticks that are lit for fragrance used popularly in South Asia[↩]

- Various perfume oils used popularly by Muslims[↩]

- A gathering or function where Muslims recite the Qur’an and qaseedas are sung[↩]

- Fast during Ramadan[↩]

- Gathering or congregation[↩]

- Your intention when praying [salah/namaz][↩]

- Legislative Assembly of Ontario, South Asian Heritage Act, 2001, S.O. 2001, c. 29 – Bill 98 CHAPTER 29: An Act to proclaim May as South Asian Heritage Month and May 5 as South Asian Arrival Day[↩]

- “Indians are simultaneously singling out in the term “South Asian/Indian” since a majority of the research conducted on the interaction between the subcontinent and Indo-Caribbeans has been from India, yet other South Asian countries and communities marginalize Indo-Caribbeans in a similar way” (Rahman 2018, 268). This is taken from my book chapter Indo-Caribbean Identity Formation in Canada: Challenges of South Asian/Indian Authenticity published in 2018 in the book Dynamics of Caribbean Diaspora Engagement: People, Policy, Practice, edited by George K. Danns, Ivelaw Lloyd Griffith and Fitzgerald Yaw.[↩]