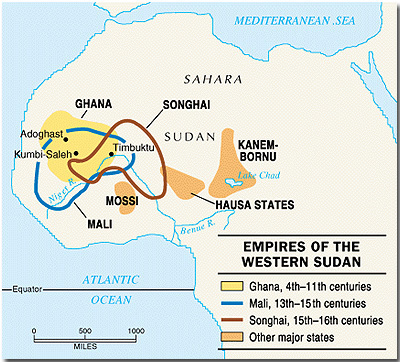

As we approach the end of yet another holy month of Ramadan and prepare to welcome the Eid-ul Fitr celebrations, it is an appropriate time to reflect on the history of Islam in Guyana. According to geographer and historian, Al Bakri, Islam reached Africa by the 8th century through the trans-Sahara trade that included the Kingdoms of Mali, Kanem Bornu, Songhai and Ghana. By the 16th and 17th centuries Islam had firmly taken hold in North, West and other pockets in Africa. Al-Bakri “painted” the following picture of the Empire of Ghana (from where the majority of our Afro-Guyanese ancestors came from) – By the year 1068 Ghana was highly advanced, economically and a very prosperous country. The “city” of Ghana consists of two towns lying on a plain, one of which was inhabited by Muslims, and possessing 12 mosques (one was a congregational mosque for Friday Jummah namaaz), each with its own Imam, Muezzin and paid reciters of the Koran. Bakri also wrote about the later influence of Islam in the Malian Empire (which included Ghana) in the 13th century under Mansa Musa, whose fame spread to Sudan, North Africa and all the way to Europe. Musa was the wealthiest ruler during that period in Africa.

It has always been a very popular but misguided belief held by many East Indians (both Muslims and non-Muslims alike), that Islam first made its way to British Guiana with the arrival of the first batch of East Indian Indentured Immigrants in 1838; however, evidence has shown this to the contrary. Islam was first introduced in British Guiana during the days of slavery when Muslim slaves from West Africa were brought by the British and the Dutch in the 16th and 17th century, to labour on the sugar plantations. Among them were the predominately Muslim nations – Akan (Ashantis), Mandingos (Mandinka) Ful (ani), Susu, and Hausa – with the latter being the largest ethnic/Islamic group in West Africa. Today, the Fulani-Hausa dominate in Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo; as well as far as Sudan in the east. It is from some of these areas that Africans were violently uprooted and transported to the “New World”, and against this historical injustice, Islam was first introduced in British Guiana.

The Fulanis were traditionally pastoral and nomadic cattle herders from Western Africa many of whom were Muslims. The term “fullah man” was derived from the word Fulani, it is also a common language for countries in West Africa, and is still being used to describe Indo-Guyanese Muslims in Guyana today, though for the most part in a derogatory way. According to Guyanese diplomat and historian, Dr. Odeen Ishmael, “It may be useful to note that some of the slaves, particularly these who came from the Fula-speaking area of Senegambia, were Muslims. Toby, a young Hausa-speaking Muslim slave in Hanover, Berbice, debated religious questions with the Rev. John Wray, the Congregational missionary in Berbice in the early nineteenth century.” Toby, who became Thomas Lewis according to the London Missionary Society, was able to read the Arabic Quran. As well, a sign of an Islamic presence among the Africans in Demerara was documented by Emilia Da Costa, author of the book, Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood who wrote that during court trial, “a slave was allowed to use the Muslim oath.”

Historical records showed that the conditions and long hours that the African slaves were forced to toil under were extremely harsh; they were subjected to severe cruelty at the hands of their slave masters on a daily basis. In addition, they were not allowed to practice their religion or to speak their respective mother tongues. And any sign of similar linguistic or cultural affiliations noticed among the slaves resulted in their segregation. Also, there was no stable family unit as relatives were purposely split up and dispersed to different plantations. Eventually, they were literally stripped of all semblances of their native life, traditions and rituals of the land of their birth. Ultimately, they were totally acculturated with the dominant forces at work, converting to the religion of their masters and in the process their African/Islamic names were also Anglicized. Thus, by the time slavery was abolished in 1834 in British Guiana any presence of Islam among the slaves had long since diminished. Nonetheless, up until the early 1830s, a number of Africans still bore their Islamic names such as—Bacchus, Mohamed, Mammadou, Sallat, Mousa, Hannah, Sabah, Feekea, Russanah, etc., as listed in the Berbice Official Gazette dating back to 1803, in which the names of a number of runaway slaves was published after being captured by bush expeditions during the years 1808 to 1810.

Despite the loss of their Islamic roots, traces of the Arabic language were referenced in the early 1800s in several books that ascribed to materials written in Arabic by the slaves that were found in British Guiana. Sylviane A. Diouf in her book “Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas”, quoted from James Rodway’s “History of British Guiana From the Year 1668 to the Present Time,” which stated that evidence of Arabic writings was supposedly found on one of the sugar plantations. According to Rodway, “in 1807 papers were found on a plantation in Essequibo, when a slave exposed a rebellion plot that was planned for Christmas Eve of the same year, based on the slave’s accusation 20 slaves were arrested and the ringleader together with a few others were hanged for their role in the “uprising”. One piece of evidence that was presented during the trial was a letter supposedly written by one of the rebel in Arabic and addressed to the slaves, however since no member of the Court could read the letter its purport could only be guessed at.”

A second book an autobiography titled “A Soldier’s Sojourn in British Guiana, 1806-1808” written by Thomas Staunton St. Clair and published in 1834, also made reference to a slave plot on the colony in 1807. St. Clair was a British soldier stationed in Demerara for three years from 1805 until June 1808. From his personal recollections he mentioned that “a slave woman who lived with a young Scottish overseer on the plantation betrayed the conspirators of a slave rebellion” and when they were captured a piece of paper written in Arabic was found in their possession. More importantly, in 1836, two years prior to the arrival of the first Hindustani Muslims in British Guiana, the London Missionary Society reported that Thomas Lewis – a freed African – was educated in England, had started a school in Union Chapel in New Amsterdam. Lewis was formerly a Muslim known as Toby who could read the Arabic text of the Holy Koran. Last, but not least the very first slave revolt in 1763 was carried by a house slave Kofi (which means born on the Jummah), he was a Muslim from the Akan tribe of Ghana,

These are clear indications that the slaves were still literate in the Arabic language and some may have perhaps still maintained some of their “Fulani” or Islamic customs – reciting from memory verses from the Holy Koran (as was in the case of Toby) and observing fasting and praying in spite of the subjugation of their slaves masters.

A blessed Eid-ul Fitr to all our brothers and sisters in Islam, especially our Afro-Guyanese in remembrance of their religious/cultural observances.

Be the first to comment on "The Arrival of Islam in Guyana – The African Muslims"