Fifty years ago, my paternal grandfather was killed. Here is the story as I recall it.

THE DAY DADA WAS MARTYRED

Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji’un – From God we come and to Him is our return.

Dua for Dada (Rasool Turab)

O Allah, forgive and have mercy upon him, excuse him and pardon him, and make honourable his reception. Expand his entry, cleanse him, and purify him of sin. Admit him into the Garden, and protect him from the punishment of the grave and the torment of the Fire. O Allah, he is under Your care and protection—safeguard him from the trials of the grave and the torment of the Fire. Indeed, You are faithful and true. Forgive and have mercy upon him. Surely, You are The Oft-Forgiving, The Most Merciful. Ameen.

Background

In the early 1970s, sugarcane farmers in Trinidad faced immense economic hardship, labour disputes, and social unrest.

1. Economic Challenges

- Low Cane Prices: Farmers were paid poorly for their sugarcane, often not even enough to cover their production costs.

- High Costs: Rising expenses for labour, equipment, fertiliser, and transport eroded any profits.

- Delayed Harvest & Payments: The Usine Ste. Madeleine Sugar Factory suffered mechanical breakdowns and trolley shortages. Farmers waited days to offload a single load of cane, often losing income and facing mounting debts.

2. Labour Issues & Union Activism

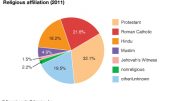

- Union Militancy: The All Trinidad Sugar and General Workers’ Trade Union (ATSGWTU), led by Basdeo Panday, was vocal in its demands for better wages and conditions.

- Government Resistance: Prime Minister Eric Williams’ administration refused to raise cane prices, viewing protests as a threat to national productivity and security. Police were frequently deployed to suppress dissent.

- Brutality: Clashes often turned violent, deepening the farmers’ sense of injustice.

3. Social & Psychological Strain

- Tension & Competition: Long waits, disputes over queue positions, and scarce resources strained relationships between farmers.

- Cane Fires: Fires—accidental or deliberate—caused devastating losses.

- Violence: Frustration and desperation sometimes led to physical confrontations.

4. The Government’s Role

- State Control: After nationalising sugar estates in 1975, the government favoured large plantations, marginalising small farmers.

- Neglect: Independent farmers had little negotiating power and bore the brunt of systemic inefficiencies.

Summary

By 1975, sugarcane farming was a daily struggle. The industry’s collapse was not just economic—it was personal, communal, and deeply emotional. Rasool Turab’s tragic death occurred against this backdrop of frustration and injustice. These factors created a hostile environment in the sugar industry in all sectors.

June 28, 1975

It was a hot, humid day. The sugarcane harvest was delayed, and anxiety filled the air. Farmers feared the rains would ruin their crops before they could be harvested. Fires had already destroyed many fields, and mechanical failures at the factory meant only two or three cane trolleys were available each day. A farmer could wait up to five days to offload a single load.

Scaling was implemented through a queue system: farmers received numbers based on their arrival time and waited for their turn. Tensions ran high. Previous strikes and protests had destabilised the process. Prime Minister Williams’ tough stance and the threat of police violence loomed.

I was with Dada (Rasool Turab) and Pa (Ashraf Ali), waiting with two loads of cane. I had just completed my O-levels (high school examinations) and, at 16, was trying to help in any way I could. Waiting at the scale felt better than cutting cane. I often told myself, “Cain killed Abel, but cane will not kill me.”

The Incident

On the left, Dada, top right, Pa and bottom right, Alim

Around midday, hope arrived in the form of three cane trolleys. But then came Rolly Havelock—a 23-year-old drunk, reckless, and arrogant. He had spent the night drinking and gambling at a rum shop inherited by his girlfriend. He was already a nuisance in the scale yard, agitated by his overnight gambling losses and all-night consumption of alcohol. Now, frustrated and belligerent, he tried to cut the line, blocking everyone else from entering the scale.

Trolley

The Checker told him to wait his turn, but Rolly refused. He parked his trailer across the entrance.

Farmers, including Dada, sat under the cantilever of Gooljar’s shop, discussing their shared struggles. Pa was farther away with another group. As Rolly’s antics escalated, everyone watched.

Rolly stormed into the scale house, confronting the Cane Weigher. It was crowded and tense. Farmers urged him to respect the system. Pa, always a man of principle, walked toward the scale house, and I followed.

Inside, voices rose. Rolly’s temper flared. Pa calmly but firmly asked him to follow the queue. Something in Pa’s words must have struck a nerve—Rolly lunged at him. They struggled and fell. Other farmers separated them, and Rolly stormed off.

We thought it was over.

Moments later, someone shouted:

“Aye, Lil Boy, run! The man coming with a cutlass, boi!”

I froze. Pa grabbed a rotting fence post and moved behind a trailer. I stayed close behind him. I was only 16, and somehow being with Pa felt like safety.

Then we heard:

“Aye, the man chop yuh fadder, boi!”

Pa rushed toward the voice. I followed. We saw Dada—his hand bleeding badly. His face was pained but calm. Blood gushed from a deep wound.

Kapil, the Pundit’s son, tore off his shirt and tied it around Dada’s hand. Blood squirted into his mouth as he tightened the makeshift bandage.

Later, we learned Dada had likely blocked the blow meant for Pa. Perhaps it was instinct. Perhaps it was love. Either way, the answer to his final question—“What are you going to do with that cutlass?”—was written in blood.

Aftermath

The crowd subdued Rolly, and the fence post found its purpose. Uncle Osman arrived with his car. Dada was laid in the back seat—Pa on one side, me on the other. He was quiet, but alert.

As we drove toward the hospital, he looked around, breathing shallowly.

Near Salamat gas station, just by Andrew’s hill, I heard it: a gurgling gasp. It was approximately 2:30 p.m.

That was Dada’s last breath. I had just witnessed my grandfather’s final moments.

The Trial

Rolly was arrested and charged with murder. But the trial was flawed. His lawyers claimed he acted in self-defence. The investigation was sloppy, with few witnesses, and the prosecution was weak.

He was convicted—but not of murder. The charge was reduced to manslaughter. He received 10 years. On appeal, just six.

Justice failed us.

The Weight of It All

That day haunted Pa for the rest of his life, as it also haunts me.

I followed my father that day, step by step, believing he would shield me. But even the strongest fathers and sons have limits.

Pa loved his father deeply. In November 1974, they agreed that Dada would retire from cane farming starting in 1975. They bought a used tractor and made two trailers. Pa stopped drinking, took on more responsibility for his parents, and focused on his children.

He worked tirelessly on that tractor, tearing down the engine, rebuilding it, soaked by rain and burnt by the sun. He wasn’t a mechanic, but he managed to make it work.

He did it for Dada. And for the future, they hoped to share.

The Man

Rasool Turab (ra)

Rasool Turab was born on August 1, 1909, to Gulgee and Turab. He married Saliman, and together they raised nine children—seven daughters and two sons.

He lived a life of hard work: raising livestock, growing food, farming cane, and working as a butcher and labourer.

He was known for his strength, once carrying sacks of wet paddy through deep lagoon mud. He enjoyed gatka during Muharram—stick-fighting with a lathi, a martial tradition rooted in Punjab.

(L to R: Ashraf [Lil Boy], KaramatAli [Jacko], Rasool, Saliman circa 1950)

A Supplication

We ask Allah to forgive and elevate Dada, to grant him peace and Jannah. May Pa and all our deceased loved ones rest in ease. May their graves be gardens of mercy, and may their sacrifices never be forgotten.

Ameen.