Although obeah (Folk Magic) was a punishable offense, it was frequently practiced as a means of inspiring or supporting slave revolt and other forms of resistance on the plantations. Both the Dutch and British viewed obeah as nothing more than witchcraft or Black magic to harm others which the “uncivilized” Africans brought with them from their ancestral villages. By the 18th century, however, European colonialists regarded obeah as a harmless superstitious practice that should be mocked instead of feared; nevertheless, the British introduced laws that made the practice a crime and in some cases punishable by death.

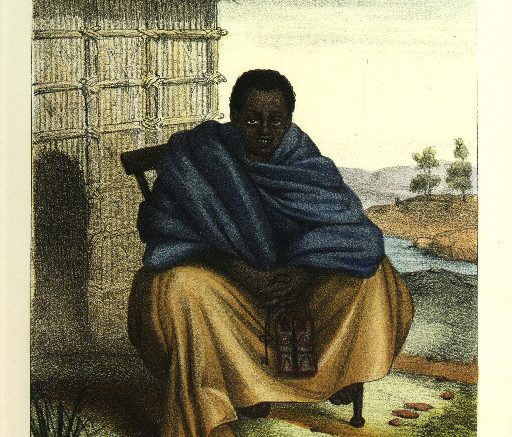

Most of the enslaved Africans in British Guiana, for the most part, relied on their own herbal cures, homemade tonics, and traditional customs. In times of sickness, many turned to African ‘healers’ using a variety of herbs and natural remedies (which in today’s world is referred to as homeopathic medications). They believed that this posed less of a danger to the ‘sick’ person than the medicine the White doctors dispensed to them. This was the case with Mamadoe, who was captured in West Africa and sold into slavery at Plantation Nigg on the Courantyne. Mamadoe was regarded as a ‘sort of doctor’ who prescribed herbal cures and remedies for those who sought his services.

Mamadoe was a Muslim who knew to recite verses from the Quran and perhaps observed the many Islamic celebrations. Imagine an enslaved African who managed to hold on to his identity – his religion and his name up until around 1824, ten years before the British abolished slavery in British Guiana, now Guyana. Mamadoe or Mamadou is the West African version of the name Mohammed and was one of the most popular names among enslaved African Muslims in the former Dutch/British Guiana (as well as in the world today). Several slaves bearing the name Mamadoe were runaways as published in several issues of the Berbice gazettes.

Sadly, on 8th November 1824, Mamadoe now old and grey, was tortured, badly beaten, and then burnt to death in his hut by another slave. At first, his death was thought to be an accident and that was why it took “Fiscal” two weeks before they looked into the matter. And then it was only when some incriminating evidence emerged (a bloody bludgeon with grey hair stuck to it) and a few slaves came forward giving eyewitness accounts on the circumstances surrounding Mamadoe’s murder.

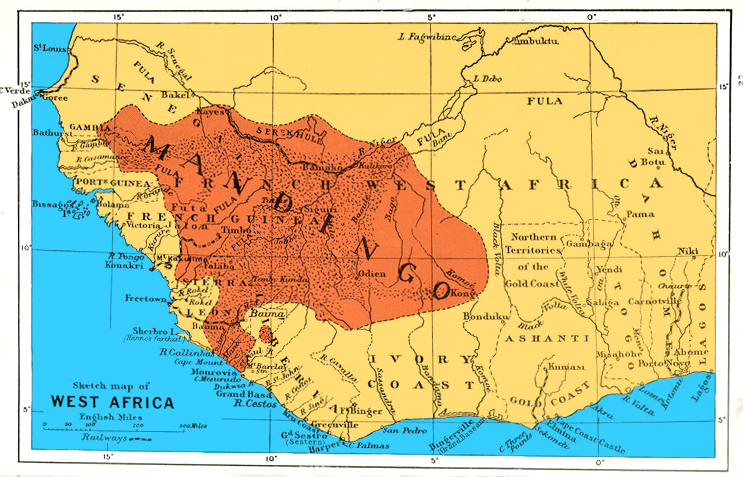

Mandingo Demographic Map – 1906

Even in his old age, Mamadoe did not sit idly. He worked as a watchman on the plantation and had his own watch hut to use at night. He prayed for the sick and offered advice on an array of issues faced by the enslaved Africans. Sadly, he was misunderstood by a group of his fellow Africans who accused him of being an “obeah man.” Sometime in early October 1824, another slave originally from Congo by the name of Tancred approached Mamadoe demanding that he saved his dying wife. Tancred really taught that Mamadoe by performing “obeah” could save his wife from an “untimely” death.

Mamadoe instructed Tancred to look for some kind of root and herbs, but he did not find any. Tancred’s countryman Rhina decided to take matters into his own hands and threatened to burn Mamadoe because that is what they do to “obeah men” in the Congo. Rhina then tied Mamadoe’s hands and gave him until the “next moon” to cure Tancred’s wife of her ailment.

When the time elapsed and the woman was not cured, Rhina carried out his threats despite the pleas of one of Mamadoe’s countryman, John Campbell, who was the only slave who stood up to Rhina despite the “cries” of Mamadoe’s wife to stop torturing her husband. Later, on that fatal day, November 8th 1824, the plantation manager found Mamadoe’s body curled up in a fetal position in his watch hut.

Mamadoe, a learned West African Muslim, was most likely from the Mandinka clan. He was a minority among mostly Congolese Africans in Guyana, and was culturally misunderstood. As well, those “scholar” who wrote about Mamadoe and obeah in Guyana, failed to ascertain that he was a Muslim who refused to adopt the name of his master and was certainly not a witch doctor but a healer.

[Editor: Over 99% of Mandinka are Muslim. Mandinkas recite chapters of the Qur’an in Arabic. Some Mandinka syncretize Islam and traditional African religions. Among these syncretists spirits can be controlled mainly through the power of a marabout, who knows the protective formulas. In most cases, no important decision is made without first consulting a marabout. Marabouts, who have Islamic training, write Qur’anic verses on slips of paper and sew them into leather pouches (talisman); these are worn as protective amulets.

For example, today in the Muslim brotherhoods of Senegal, marabouts are organized in elaborate hierarchies; the highest marabout of the Mourides, for example, has been elevated to the status of a Caliph or ruler of the faithful (Amir al-Mu’minin). Older, North African based traditions such as the Tijaniyyah and the Qadiriyyah base their structures on respect for teachers and religious leaders who, south of the Sahara, often are called marabouts. Those who devote themselves to prayer or study, either based in communities, religious centers, or wandering in the larger society, are named marabouts. In Senegal and Mali, these Marabouts rely on donations to live. Often there is a traditional bond to support a specific marabout that has accumulated over generations within a family. Marabouts normally dress in traditional West African robes and live a simple, ascetic life.]