Speech given at the Trinidad and Tobago Fifty Plus Club on Sunday 29th May 2011, the Birkdale Community Centre, Ellesmere at Brimley, Toronto.

I got a call in my office late last night from my wife asking how I would feel giving a short speech to the Fifty Plus Club, today Sunday. Everald Seupaul had phoned, looking for me, and she relayed the request. Short notice, we both agreed, but hers was a suggestion, then taking hints from our conversation, I realized that it was an order, that I had an obligation, for we both have deep respect for the work of this organization and what it stands for. So I said yes, and she called Everald to say so. Then for the rest of the wee hours of the morning, without writing down a word, I worked out a mental strategy as to how I should approach this delicate yet heartfelt subject called Indian Arrival Day.

I decided to personalize it, to give you anecdotes of my childhood experience, my teenage years under the family tutelage, and to highlight the Indian experience.

I am sure almost all of you will identify with snippets here and there.

First, you must know something about me, a boast for sure, but it is important to tell you this fact.

My father was born in Claxton Bay, became a lifelong school teacher, well noted for his correctness of the English language. Our house was full of books and magazines, and I at a tender age, struggled to decipher words and meanings, so much so that by the age of four, I could actually read a long sentence. A whole world beyond the home began to open up.

I particularly enjoyed those colourful Life Magazines and plus we had many old World War II issues, and I asked numerous questions about tanks and planes and a man name Hitler.

Somewhere between the age of five and seven, I spent a few weeks at my father’s sister in Barrackpore. I discovered for the first time an aspect of Indian-ness, something innate from which I had sprung.

I am sure you will agree with me that Barrackpore is as culturally and emotionally close to India as you can get in the Caribbean.

There was something else too.

On an end table, a piece of furniture we called a “tallboy” was a large hardcover book, reddish brown, and a bit dusty. Apart from my cousins’ school books, I believe that this was the only coffee table book in the entire house.

I opened it, and began to read, and read, and read. I could not put it down.

The book was the 1945 picture edition of the 100th anniversary of the first arrival of Indians in Trinidad, and there was a huge celebration in Skinner Park, San Fernando. I recognized names that my parents spoke of.

What a treat it was to see people’s names that you knew, and even met, especially as my mother’s side of the family were small haberdashery traders.

And thus I began a lifelong quest of asking everyone and anyone what they knew about those years of arrival. And I guess that I’ll do so until I die.

In those years too, my mother’s family commemorated two days of the year, beyond the statutory holidays of the time. One was Indian Independence Day, and the other was the first Indian arrival in Trinidad.

We would rig up a broomstick on a fence in front of my grandparents’ house in Belmont and fly the flag of India.

You see, all serious conversation dealt with our eventual return to the Mother Country. My grandmother, even though she was born in Gasparrillo, Trinidad, referred to India as “home”. That she had an arranged marriage with a man from India at the tender age of nine, but she did not live with him until fifteen, and went on to have seven children.

Parallel to this wishful aspect of our social and religious life, we pursued our daily lives; the children went to school, we conducted our commerce, and just about everything revolved around weddings and baptisms. The family was growing.

After my grandfather died, talk of “going back to India” evaporated.

But India was still very much with us in the persons of those indentured who could be seen, more so in south Trinidad.

I would go to my cousins in Princes Town, we are still in the 1950s, and encounter many men walking on side roads, almost all wearing kapras, or dhotis, some with turbans, some carrying lotas and almost all sporting a walking stick, which I was told was mostly made of local poui wood. They tended to congregate around street stand pipes and speak in their Hindustani language. I listened in on their conversation, not understanding anything, but enjoying the musicality of their language nevertheless.

Also, there is an account of a distant uncle who returned to India, and as he was about to board his ship, flung his stick into the sea, his final break from his sugar cane labours. I try, even to this day to create an artist’s impression of that ship returning with hopefuls.

And then there were two things traumatic, almost simultaneously. I was about nine or ten years old at the time.

Firstly- I heard my aunts describing the travails of another relative – everybody was called uncle then. I heard that on a sugar cane estate, he was flogged by an overseer for being too lazy.

That little snippet of information caused me enormous anger, an anger that resides within me to this day. I have surmised time and again, that if I were African, and to know the horrors of slavery inflicted on my forebears, then I would be a very, very militant man indeed. It is through this related experience of that so-called lazy uncle, I began to understand what victimization is all about.

Secondly- My grandmother, now a widow, and her daughters, that is, my aunts would gather in her home once a month and cook huge pots of food, rice, rotis, curries of all types, then assemble meals in brown paper bags and they would hire a taxi, or taxis to take them to San Juan just outside the market close to the Croiseé. I accompanied them.

It was perhaps the most demeaning sight to my culture and what my immediate family stood for.

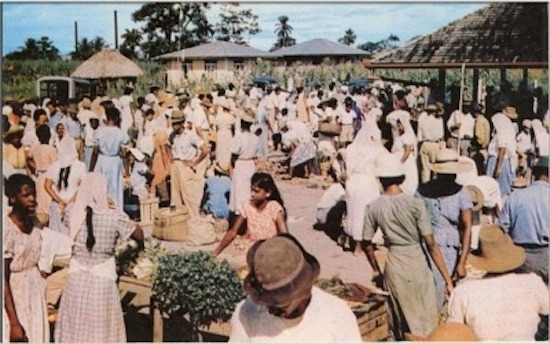

Indian Vagrant in Port of Spain, Trinidad circa 1903

There, as far as my little eyes could see, along the Eastern Main Road was a very, very long line of beggars, possibly a thousand or so, in faded rotting rags. They were all Indians, very old, and as I later surmised, most would have come from India. They were haggard and emaciated. These were the dregs of humanity, the outcasts of an economic movement that brought riches to many, but built on the backs of these unfortunate souls. They who had given their labour, the best of their years, were now abandoned, many cheated out of their gift of a piece of land, or a home, or an ajoupa, or even a jute bag under a galvanize shed.

The writer V.S. Naipaul wrote of similar experiences when he and his father, Seepersad, walked through Woodford Square a decade earlier.

Thus it is recorded, but I am a witness, and I believe some of you have experienced this too.

Yes we fed them, but one meal on a Sunday was not enough. How they lived beyond this, I do not, and how they died, and how their rotting bodies were disposed of, I do not know.

Those Sunday experiences have moved me far, far greater than any laudatory speeches about Indian success stories, or grand celebrations, or prayers, or even grand monuments.

A rotting ship beached on the shores of Trinidad or the rest of the Caribbean for that matter, those that came across the Kala Pani, is a more fitting monument to our ancestors who braved everything in search of a better life.

This is what Indian Arrival Day means to me, and I would hope that stories like those be told to the young ones, that they would not be doctors and lawyers, and multi-millionaires,were it not for our ragged besieged and abused ancestors.

We may be well off in this country and even in Trinidad or Guyana or the rest of the Caribbean, but let us not forget the humility of our existence.

I thank you for this opportunity to speak to you today.

Be the first to comment on "MY PERSONAL EXPERIENCE WITH INDIAN ARRIVAL DAY."