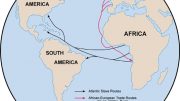

Muslim slaves – involuntary immigrants, who had been the urban-ruling elite in West Africa – constituted at least 15% of the slave population in North America in the 18th and 19th centuries. Their religious and ethnic roots could be traced to ancient black Islamic kingdoms in Ghana, Mali, and Sohghay. Some of these West African Muslim slaves brought the first mainstream Islamic beliefs and practices to America by keeping Islamic names, writing in Arabic, fasting during the month of Ramadan, praying five times a day, wearing Muslim clothing, and writing and reciting the Qur’an.

Muslim slaves – involuntary immigrants, who had been the urban-ruling elite in West Africa – constituted at least 15% of the slave population in North America in the 18th and 19th centuries. Their religious and ethnic roots could be traced to ancient black Islamic kingdoms in Ghana, Mali, and Sohghay. Some of these West African Muslim slaves brought the first mainstream Islamic beliefs and practices to America by keeping Islamic names, writing in Arabic, fasting during the month of Ramadan, praying five times a day, wearing Muslim clothing, and writing and reciting the Qur’an.

The Bilali Document of Bilali Muhammad

Georgia Sea Island slave, Bilali. He was one of at least twenty black Muslims who are reported to have lived and practiced their religion in Sapelo Island and St. Simon’s Island during the antebellum period. The Georgia Sea Islands provided fertile ground for mainstream Islamic retention thanks to their relative isolation from Euro-American influences. Bilali was noted for his devotion, for wearing Islamic clothing, for his Muslim name, and for his ability to write and speak Arabic. Moreover, available evidence suggests that he might have been the leader of a small local Black Muslim community. Islamic traditions in his family were retained for at least three generations. By the eve of the Civil War, the old Islam of the West African Muslim slaves was for all practical purposes defunct, because these Muslims were not able to develop community institutions to perpetuate their religion. When they died, their version of Islam, which was African-American, private, and with mainstream and heterodox practices disappeared.

Early 20th-Century Mainstream Communities

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries,, the Pan-Africanist ideas of Edward Wilmot Blyden (1832-1912), which critiqued Christianity for its racism and suggested Islam as a viable religious alternative for African Americans, provided the political framework for Islam’s appeal to black Americans. Moreover, the internationalist perspective of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association and the Great Migration of more than one million black southerners to northern and Midwestern cities during the World War I era provided the social and political environment for the rise of African-American mainstream communities from the 1920s to the 1940s. The Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam, a heterodox missionary community from India, laid the groundwork for mainstream Islam in Black America, by providing African Americans with their first Qur’an, important Islamic literature and education, and linkages to the world of Islam.

Shaykh Daoud Ahmed Faisal

Black Sunni Muslims can trace their roots in the United States in the early 20th century to two multi-racial communities: the Islamic Mission of America, led by Shaykh Daoud Ahmed Faisal in New York City, and the First Mosque of Pittsburgh. Influenced by the Muslim immigrant communities, by Muslim sailors from Yemen, Somalia, and Madagascar, and by the Ahmadi translation of the Qur’an, Shaykh Daoud, who was born in Morocco and came to the United States from Grenada, established the Islamic Mission of America, also called the State Street Mosque, in New York City in 1924. This was the first African-American mainstream community in the United States.

Shaykh Daoud’ s wife, “Mother” Khadijah Faisal, who had Pakistani Muslim and black Caribbean roots, became the president of the Muslim Ladies Cultural Society. The Islamic Mission of America published its own literature, including Sahabiyat, a Muslim journal for women. This influential community spread mainstream practices among black Muslims on the East Coast in the 1920s and 1930s and continued to be significant to African-American Sunni Muslims for the remainder of the 20th century.

The First Muslim Mosque of Pittsburgh:- al-Masjid al-Awwal is located in the Hill District of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

The First Mosque of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was established in 1945 by African-American Muslims who wished to spread the teachings of Islam; build mosques; establish the Jumu’a prayer in their community; aid its members in case of death or illness; and unite with the Muslim communities in the United States. This mainstream community was the result of a spiritual metamorphosis after its previous associations with the heterodox philosophies of the Moorish Science Temple and the Ahmadiyya. In the 1950s, they established Young Muslim Women’s and Young Men’s Muslim Associations which provided social services to the local community. Eventually, the First Mosque of Pittsburgh issued sub-charters to African-American Sunni communities in several other cities.

In the early 20th century, in addition to these two African-American communities, there is strong evidence of a vibrant multi-racial mainstream Islamic community in New York City, which included black Americans, African, Turkish, Polish, Lithuanian, Russian, Indian, Albanian, Arab, Persian, and Caribbean peoples. But this multi-racial model, which also developed among Sunni Muslims in the mid-western United States, does not suggest a race and color-blind community experience, as immigrant Muslims were noted for their ethnic, racial, and linguistic separation from African-American Muslims during this period. Finally, these early African-American Sunni communities were overshadowed by the successful missionary work of the heterodox Ahmadiyya and later by the ascendancy of the Nation of Islam in the 1950s. Mainstream Islam did not become a popular option for African-American Muslims until the 1960s.

Mainstream Islam in Contemporary Black America

Malcolm X

Large numbers of African Americans have turned to mainstream Islamic practices and communities since Malcolm X’s conversion to Sunni Islam in 1964 and his establishment of the Muslim Mosque, Inc. in New York City. Like Malcolm X, African-American Sunni Muslims see themselves as part of the mainstream Muslim community in the world of Islam and study Arabic, fast during the month of Ramadan, and pray five times a day. The dramatic growth of Sunni Islam in black America is also related to the arrival of more than one million Muslims in the United States after the American immigration laws were reformed in 1965.

Elijah Muhammad’s son, Warith Deen Mohammed, has played an important role within mainstream Islam in the United States. He became the Supreme Minister of the Nation of Islam after his father’s death in 1975. During the first years of his leadership, he mandated sweeping changes, which he called the “Second Resurrection” of African Americans, in order to align his community with mainstream Islam. He refuted the Nation of Islam’s racial-separatist teachings, and praised his father for achieving the “First Resurrection” of black Americans by introducing them to Islam. Now the community’s mission was directed not only at black Americans, but at the entire American environment. The new leader renamed the Nation of Islam the “World Community of Al-Islam in the West” in 1976; the “American Muslim Mission” in 1980; and the “Muslim American Community” in the 1990s. Ministers of Islam were renamed “imams” and temples were renamed “mosques” and “masajid.” The community’s lucrative financial holdings were liquidated and mainstream rituals and customs were adopted. Although Warith Deen Mohammed’s positive relationships with immigrant Muslims, the world of Islam, and the American government are important developments in the history of mainstream Islam in the United States, his group has diminished in members since the 1980s.

Daryl Islam, founded in Brooklyn, New York, in 1962 and having branches in many major American cities, is probably the largest and most influential community of African-American Sunni Muslims. The Dar’s practices and community experience focus on the utilization of the Qur’an and habit. The members of the community do not follow the teachings of a particular contemporary leader. Prestige and leadership are based on knowledge of the Qur’an, the hadith, and the Arabic language. Darul Islam is a private decentralized community, which did not allow immigrants in its midst until the mid-1970s. The Hanafi Madhhab Center, founded by Hammad Abdul Khalis in the 1960s, is an African-American Sunni group that made headlines in the 1970s because of its conversion of the basketball star, Kareem Abdul Jabbar, and the assassination of Khalis’ family in their Washington D.C. headquarters.

Although African-American Muslims populate multi-ethnic Sunni masajid and organizations across the United States, reportedly there are subtle racial and ethnic tensions between African-American and immigrant Muslims today. Immigrant Muslims talk about “a color and race-blind Islam” and the American dream, while African-American Muslims continue to place Islam at the forefront of the struggles for social justice, as the United States enters a new century of frightening racial violence and corruption. Certainly, African-American and immigrant Muslims have a lot to learn from each other and need to present a united front on social justice issues, because mainstream Islam’s appeal and ascendancy in the United States in the next century may depend on American Muslims’ ability to claim a moral and political high ground on those social justice issues that have historically divided the American Christian population.

Mainstream Islam has deep roots in the African-American experience, roots that reach back to the history of slavery and early 20th-century black Sunni communities in the United States. How has the issue of race in the United States affected the practices and the community experiences of black Sunni Muslims who traditionally see Islam as a color and race-blind religion?

Malcolm X’s Hajj in 1964 and Warith Deen Mohammed’s transformation of the Nation of Islam into an orthodox community in 1975 are two of the more recent visible signs of the importance of mainstream Islam in the African-American experience. African Americans comprise about 42% of the Muslim population in the United States, which conservatively is somewhere between four to six million; and Sunni African-American Muslims are the predominant community in the United States today. Yet, the involvement of black Americans with mainstream Islam is not a recent phenomenon.

Be the first to comment on "Mainstream Islam in the African-American Experience"